Prof. Sylvia Rosila Tamale is a Ugandan academic, and human rights activist. Tamale received her Bachelor of Laws from Makerere University, Master of Laws from Harvard Law School, and Doctor of Philosophy in sociology and feminist studies from the University of Minnesota in 1997. She was the first female dean in the Law Faculty at Makerere University. In her latest masterpiece of scholarly work, she dives to the deep end of the debate on decolonisation and Afro-feminism. On assignment from the East African Center for Investigative Reporting’s online publication, Vox Populi, Joel Mukisa, a student of law at Makerere University, sat down with her for an exploratory fireside conversation on her new book.

How did you get started on this whole book, Decolonisation and Afro-feminism?

Well, I am 58 years old and in 2022 I am set to retire from my academic career of almost 30 years. So I felt it was my duty, my responsibility, to put down the knowledge I had acquired over the years in a book. I’m hoping that it will also serve as an educational text for trans-disciplinary teaching but actually the book is quite different from the one that I initially set out to write. The more I delved into researching and writing, the more I discovered that there was a lot I didn’t know. A lot. I have always tried to be critical of colonial discourses and capitalist patriarchal oppression but I had no idea how powerful and all-encompassing coloniality was.

I had not fully appreciated how pervasively coloniality seeps into every crevice of our lives and takes hold of our thinking processes and our ways of being. So if a professor like me does not fully understand the subtle workings of colonialism and coloniality, what about your ordinary person out there? We think we are educated yet what we are doing is perpetuating systems of power that are marginalising. We have invisible puppeteers pulling the strings from across the oceans in the shadows of religion, law, language, globalisation, and so on.

So as educators I think that we are directly implicated in student outcomes and I needed to redeem myself.

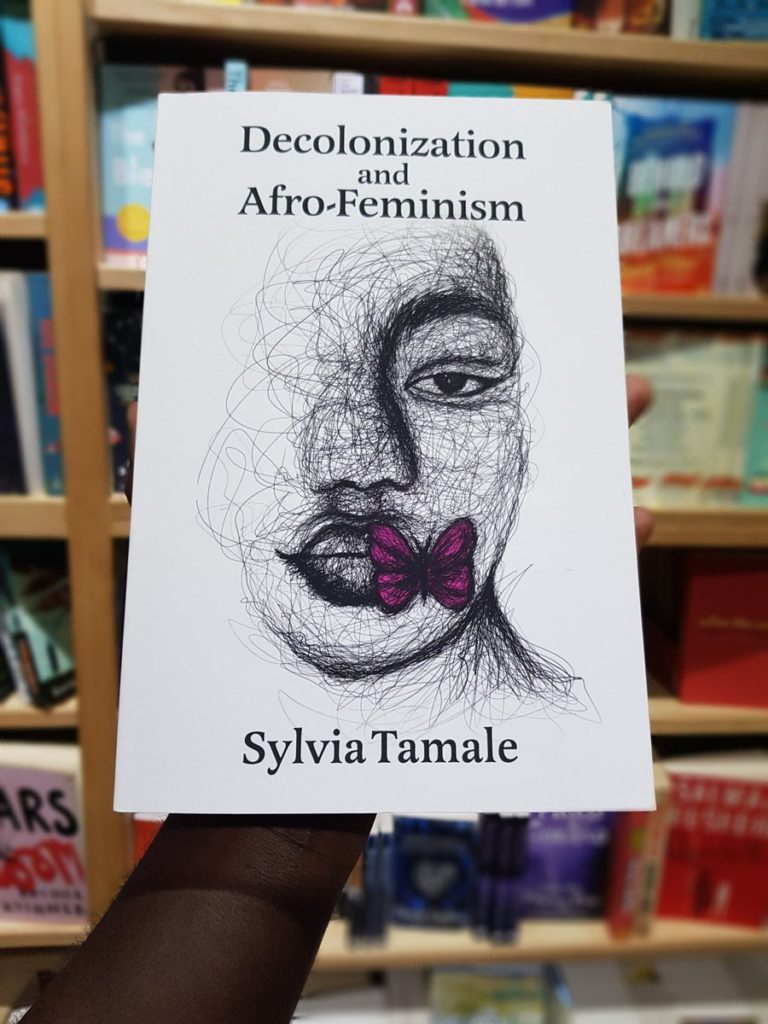

The book cover is intriguingly beautiful. Tell us what it means to you?

You have no idea how many hours I spent on the internet searching for a cover image that would convey de-colonisation and afro-feminism in one go. I got a few candidates but they were not very satisfactory. They were either too cliched or stereotypical or uninteresting. I remember I even asked my artist son to design something for me. It was good but not quite one hundred percent.

Then one day I happened upon this image and immediately knew that this is it. So you can imagine the double joy when I discovered that the artist was an African woman, Joy Orgunpolo. She’s Nigerian. We contacted her for permission to use her image and she graciously granted it without asking for payment. There is something about scribble art that brings together so many elements in a simple yet powerful style.

For me, that seemingly chaotic scribble symbolises the mental confusion and physical pain that Africa is experiencing. And yet, from what appears to be chaotic or messy emerges a perfectly detailed beautiful expressive and dynamic image of an African woman representing hope, representing new beginnings for a continent. Now the butterfly on the corner of her lips for me symbolises metamorphosis and transformation. The butterfly spirit of a new life. The woman embodies the agency of the African woman in spearheading transformation.

I remember we requested artists to redraw the image in high-resolution for the book cover and that process was quite hilarious because Joy kept sending me images that didn’t quite match her original image. Either the nose had turned into a short muzungu one or it had lost that authoritative look that attracted me to the image. So I kept rejecting the new editions. Joy was extremely understanding and fully emphasised the need to get it right. She was simply amazing. I love that woman!

What inspired you to use the term Afro-feminism in your title?

I am aware that there are several variances of feminism in Africa – of course based on ideological and contextual differences. I chose the term Afro-feminism as an all-encompassing strand of de-colonial feminism. I think that it weaves together all feminist efforts on the continent that go beyond addressing the practical needs or the strategic interests of African women within the existing oppressive structures. And also challenges the power structures that are embedded in social structures, knowledge production, global economy and so on. Afro-feminism is not limited to addressing oppression based on gender alone but analyses the complex and dynamic ways that gender intersects with European hegemonic oppression based on race, sexuality, disability, spirituality and so on. So it strives for radical transformation.

You also say that your book focuses on British colonialism. There’s obviously been various European colonial powers on the continent, but within that, there were also various forms of colonialism such as direct rule and indirect rule or native administration. How did you feel you would address these different challenges in the book and was it something you felt might be a challenge?

Whether British imperialism adopted the form of settler colonialism or indirect rule on African soil, the ultimate purpose was the same. That is exploitation and appropriation of natural and human resources of the continent. So the adoption of direct or indirect rule was based on issues such as climate or geographical accessibility, disease and so on, but all were brutal, all were exploitative so it is really substance over form as they say in accounting.

So this book doesn’t really focus on the legal differences of the methods the British employed to govern the different territories that they were allocated in Berlin in 1884. They had convinced themselves and they had convinced the world that they were on a noble civilising mission on the “dark continent”. So the infrastructural form of colonialism in Kenya, Zimbabwe, or South Africa – where they practised settler colonialism – may have been different from that of Uganda, Nigeria, Ghana and so on where they governed through indirect rule. But you know what? At the end of the day, they preyed on all of us the same way. They exploited, they denigrated, devalued our ways of knowing and our ways of being the same way. They were reading from common colonial policies.

You propose Ubuntu as an indigenous African philosophy and way of life that emphasises humane existence with the whole ecosystem. How do you think this Ubuntu philosophy can engage with power structures? Some feminist critiques say that Ubuntu undermines female empowerment. So how do you think Ubuntu can be used in scholarship to undermine patriarchy?

Instead of talking about patriarchal privilege, I prefer using the intersectional term patriarchal capitalism because both systems cling on each other for support and survival. They are like siamese twins – one heart, different limbs but really they support each other. So while the moral and ethical foundation of patriarchal capitalism is based on exploitation and denigration, especially of woman, that of Ubuntu is primarily based on compassion.

While the earlier system promotes individualism, the latter endorses collective action and emphasises interdependence. So it is easy to see how Afro-feminism can invoke Ubuntu to undermine patriarchal capitalism. Ubuntu is a philosophy. It is also a way of life, but it is well understood in most African traditions. The book joins many other African feminists who implore us to unwed our conceptual fitting from Western social ideals and trust our traditional epistemologies as legitimate, as authoritative.

Now, thanks to coloniality, most of us have internalised the notion that anything African is unworthy. Ubuntu I think can be invoked in our theorising about gender relations and for adopting principles of justice that can give more weight to the well being of groups such as women and other marginalised groups. So in the book I urge African feminists to revitalise and to repurpose the values enshrined in Ubuntu – for example humaneness, communitarianism, and egalitarianism. To repurpose these in our struggles for gender justice.

Ubuntu represents possibilities for and about our humanity as African people. I think we need to inculcate these principles into our children. From when they are very small, teach them that if you denigrate or humiliate a human being, you’re also denigrating yourself as part of the greater whole. So in other words, you are because they are. I am because we are. But when it comes to issues of gender based violence, I must emphasise that patriarchal privilege cannot be fully undermined without addressing those deep structural barriers that undermine women. Including gender-based violence, neo-liberal capitalism, resource redistribution, education, law, religion and so on. Those must be tackled in tandem.

You refer to intersectionality as an important analytical framework for addressing those different interlocking identities as well as structures. You also refer to intersectionality to refer to different structures of oppression. These would include law, economy and religion, etc. What do you think are the implications of using the same word or framework to address both of these things? Because identities and structures are used in different ways, at different times, and someone’s identity doesn’t necessarily tell us about which structure is significant. So these are big issues. What is your take on that?

Thinking intersectionally means that you are always aware of the multiple identities and experiences that people have, as well as the complex levels that power and privilege operate from. I don’t see any tension in encompassing both domains in the same construct. I believe that an intersectional understanding of both identities and structures simply lends clarity to what we need to do in dismantling the interlocking structures of oppression. Now just two weeks ago, Caster Semenya, a South African athlete whom I write about in chapter four, lost her appeal for equal treatment in the Swiss supreme Court. This was a clear example of the double standards employed by the IAAF.

They employ double standards on the advantages enjoyed by Semenya on one hand and for example the swimmer, Michael Phelps on the other. Semenya’s multiple identities as a gendered woman “socially and culturally”, and in the other hand a man, “legally, and biologically” can only be understood through an analysis of the multiple structural dimensions of culture, law, and science as they were applied by the colonial body politic in Switzerland.

At one point in the book you have a critique of human rights – the universalism inherent in human rights and the insufficient focus on gender equality as a way of addressing the challenges that women in so many parts of our continent face. You propose an emphasis on different but equal complementarity as a way of addressing violations, inequalities and so on. Tell us more about that.

Yes I talk about different but equal complementarity. I can see how invoking that argument can easily be misread as binary gender essentialism in this context. As I argue elsewhere in the book, the notion of gendered men and gendered women are not only limiting, but they are based on exaggerated portrayals of gender difference. So here, I was trying to argue that we should reduce the complimentary attributes that our heterogeneity as African people brings to the development and liberation project of our continent. In the spirit of Ubuntu.

But what does complementarity refer to here?

It is certainly not referring to the biological attributes, but in our diversity, we complement each other. And as we struggle for liberation, we bring different values to the project. Maybe it didn’t come out very well but that’s what I was trying to say.

You also critique the whole notion of universalism in human rights. Why is that a problem and how has it featured in some arena that we need to be aware of, thinking about decolonisation and decoloniality?

When you talk about human rights and the notion of gender equality, these are enshrined in international, regional and national legal documents and they sound very logical and are attractive. We have all advocated and struggled for gender equality and human rights. But a closer look at these concepts using the lens of coloniality reveals the historical smudges that taint the concept of rights and the concept of equality. Which explains why, despite our best efforts and our highest hopes, very little has changed for the majority of African women. So I really think that we need to get off the hamster wheel and address the real obstacles.

The term gender, within the concept of gender equality, takes off from the problematic premise of essentialised homogenous women who are supposed to suffer oppression in the same way. And then, equality, within that paradigm of universalised human rights, is also conceived as the same or equivalent. In the book I examine the history of treaty-based human rights, showing their core purpose and their enforcement agenda. Their ideological orientation is largely based on Western liberal, individualistic understanding of rights rather than in underscoring the critical vitality of group rights, and that is why I strongly believe that African feminists should adopt strategies that reflect Afrocentric world views like Ubuntu, which is likely to engender real gender justice that affirms social diversity.

You also write about the challenges of working within an institution like the academy, which is supposed to be about knowledge building yet in practice so often it does not deliver. You also talk about gender and women’s studies as a way of trying to produce knowledge that is informed from a feminist perspective. To what extent do you think that actually happens and how have you navigated the difficulties of having to do that within the various constricting dimensions of the university?

Oh it is very tough. You know the African university, as we all know, is really a relic of colonialism and it is constructed by men for men and, to date, we still see that power in the hierarchies and the institutionalised masculinity within the institution of the Academy. So it is extremely difficult. It’s always a game of push and pull – pulling the rope for women to voice the legitimacy of their work, especially feminist work, within the academy. It is always taken as something that is not very serious. We are always pushing and there are so many subtle institutionalised ways, micro politics that go on within the academy. You may not find the Vice Chancellor saying that women studies or gender issues have no place but it’s the subtle micro workings of how the University operates.

In Makerere (University), like the rest of the country, we have very many good policies. So we have a gender policy here, we have a sexual harassment policy. Having them is one story, their enforcement and implementation is a totally different story. But also, when it comes to the directorate for example, we have a Directorate of gender mainstreaming here at Makerere. It is not supported. It is one of the bodies that is least supported, financially, so you find that it is very difficult to advocate for issues of gender in a masculinity institution like the academy. We are always fighting and many other feminists in their universities around the continent know this.

You talk about the need for interdisciplinary feminist knowledge, the need to work across different boundaries of discipline, ways of thinking, etc. How do you think it might be best approached in terms of pedagogy and content for curricula in African universities?

In the book I give the example of the Marcus Garvey Pan-Afrikan University which was founded by Professor Wadada Nabudere in Eastern Uganda and he tried to implement what he was preaching about trans-disciplinarity. So in addition to having lecture halls on campus, they also have off-campus centres where students engage with local communities and they also bring the local communities in the four walls of the lecture hall. So they learn using different epistemologies, different methods, pedagogical references.

The problem is our mainstream regulatory bodies like the National Council for Higher Education (NCHE) still think in that colonial framework and they don’t think that is real education. So they have denied, for example, this Marcus Garvey University a practicing certificate. They haven’t commissioned it yet. But it is possible. I think what we need is awareness. To say that this siloed disciplines, really what they give us is a frog’s eye view of our problems, of the world.

If you’re only studying mathematics, or law or geography, you fail to see how they interconnect and how they affect us as Africans. So what we need is a hawk’s view. To be up their soaring in the sky and looking down, having a very clear picture of what our challenges are and how they interconnect. That’s why interdisciplinarity is very important. We just need to be aware of what trans-disciplinarity is and how these siloed disciplines really just engender coloniality and move away from it.

I have a niece who did mathematics up to university. And she was a very good student and she would get ‘A’ stars and everyone was fighting for her. Apparently with mathematics you can solve any problem in the world so you can imagine a mathematician who is also endowed with sociological knowledge and art and think how much that person would be. Especially being able to peel away these colonial blinders that stop us from seeing clearly what it is we need to get rid of in order to move on.

Writing this book really gave me a 2020 vision of where we need to be. And as I said earlier, I am a professor and I am supposed to know these things but I didn’t. So, I think these siloed disciplines are some of what we have and we just need to understand that having a degree in law doesn’t make you the greatest person in the world, actually you could be very ignorant.

What are your thoughts on addressing restricted access to what is already produced out there, with the view to producing more liberating knowledge?

I really think that it is criminal to commodify knowledge. None of us, nobody can claim to be the original creator of knowledge. There is no genius that exists on planet earth who can claim original knowledge. We all build on existing knowledge. We all know the old saying that if you copy one author, that’s plagiarism. But if you copy several, that is research. Our conclusions are based on knowledge that we collect from others. You go out and interview people, and so on and so forth. So it is criminal to claim knowledge as exclusively individual and to profit from it.

It is true that publishers incur costs. Publishing, copy editing, distribution, etc. But it is one thing to recoup such costs, and it’s another to appropriate knowledge for profit and enrichment. And this is mainly through intellectual property laws or over pricing intellectual publications. These days digital publications are not as expensive as paper publications. So for me it was extremely important that my book is available to the reading public for free.

I think that African governments, it’s incumbent upon them, if they are serious about decolonisation, to fund scholarly publications which counter hegemonic colonial knowledge. If the funding comes from government, there is no need to make profits. Because what we really need is awareness. We need to spread awareness about decoloniality as widely as possible. That is one of the four main objectives.

My main goal for writing this book was to symbolically open a door and force a confrontation with those comfort zones that we have constructed around various issues we have for long taken for granted. We sit in our comfort zones and take things for granted. So my main four messages were – Africa’s transformation requires radical clarity, and understanding of the deep legacies of colonialism and imperialism and patriarchy. Secondly, that as Africans, we need to rethink and re-conceptualise our feminist work by placing it in a decolonial framework that illuminates the relationship between gender, race and normative sexuality. Thirdly, I wanted to bring out the fact that such understanding must be popularised and followed by a re-culturalisation and re-humanisation of all black people around the world wherever they are found. And finally, that all efforts to liberate our continent should be inclusive and Pan-Africanist in nature.