BY DAVID LUMU

The arrest and detention of Kyadondo East MP, Robert Kyagulanyi aka Bobi Wine, the former presidential flag bearer for National Unity Platform (NUP) on November 18, 2020, found me en-route to Entebbe from Kireka.

I wanted to map out my journey. But I didn’t reach. Kampala city was burning. Demonstrations and protests over the arrest of Bobi Wine had turned riotous and rowdy.

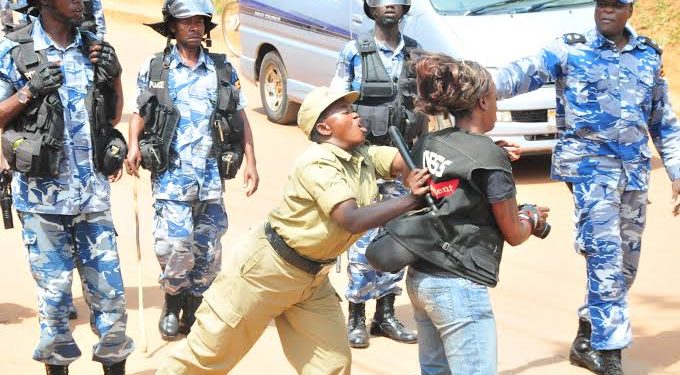

Security officers were shooting aimlessly like a monkey armed with a loaded gun. The rioters were also on rampage like an injured tiger. They blocked roads, damaged Government and private vehicles, punished ‘National Resistance Movement (NRM) supporters’ for wearing yellow, the colour of the ruling party and engaged in endless running battles with Police.

Everyone, I think, yearned for the update. And here is why the media is important—the public expects journalists to provide prompt and in most cases ‘live’ streaming of events in circumstances of this nature.

Yet as usual, no media house dared to relay the events live. Reason: The State, especially ours under the NRM, does not want noise makers when they are executing their gory and dark world affairs.

NBS TV, a private media platform known for live coverage of events, was ‘conspicuously’ blind to the November 18 events. When NTV, another private media outlet, attempted to capture the events, the Police pounced on the reporters and also confiscated all the equipment, including the camera.

George Orwell said many years ago that: “Journalism is printing what someone else does not want printed: Everything else is public relations.”

In many ways, the greatest weapon, media experts argue, is not a gun or a bomb. “It is the control of information. To control the world’s information is to manipulate all the minds that consume it.”

The arrest of Bobi Wine and the treatment of journalists attached to cover his campaign trail, speaks volumes about the state of press freedom in the country.

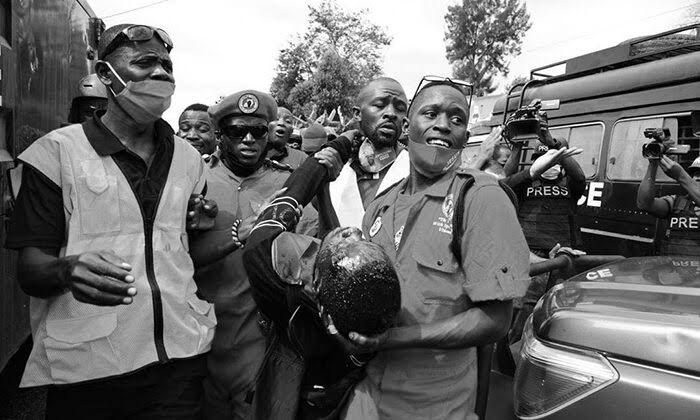

“He is a journalist. He is a journalist,” scribes shouted as police executed the arrest of Ghetto TV’s Ashraf Kasirye on November 18. In subsequent campaign tours, Kasirye was badly injured, wheeled off the campaign trail and permanently admitted to-date (he has since recovered from coma).

During campaigns, Ghetto TV would relay live coverage of Bobi Wine tours. On other hand, to buffer their excessive use of force, security accused Bobi Wine of violating a raft of guidelines that Government rolled out to curb the spread of COVID-19.

Sam Balikooowa, another journalist who was arrested, suffered a straight dismissal from City FM in Jinja by his boss, Moses Karangwa, the Kayunga NRM chairperson of Kayunga district. Reason for dismissal: Airing opposition related news, especially covering Bobi Wine.

Enter February 17 (post-electoral period)

Fast-forward in the post-electoral period. Security excesses continue to take shape. On February 17, 2021, about eight journalists were again clobbered as they covered Bobi Wine’s submission of the list of alleged detainees to the United Nations office in Kololo.

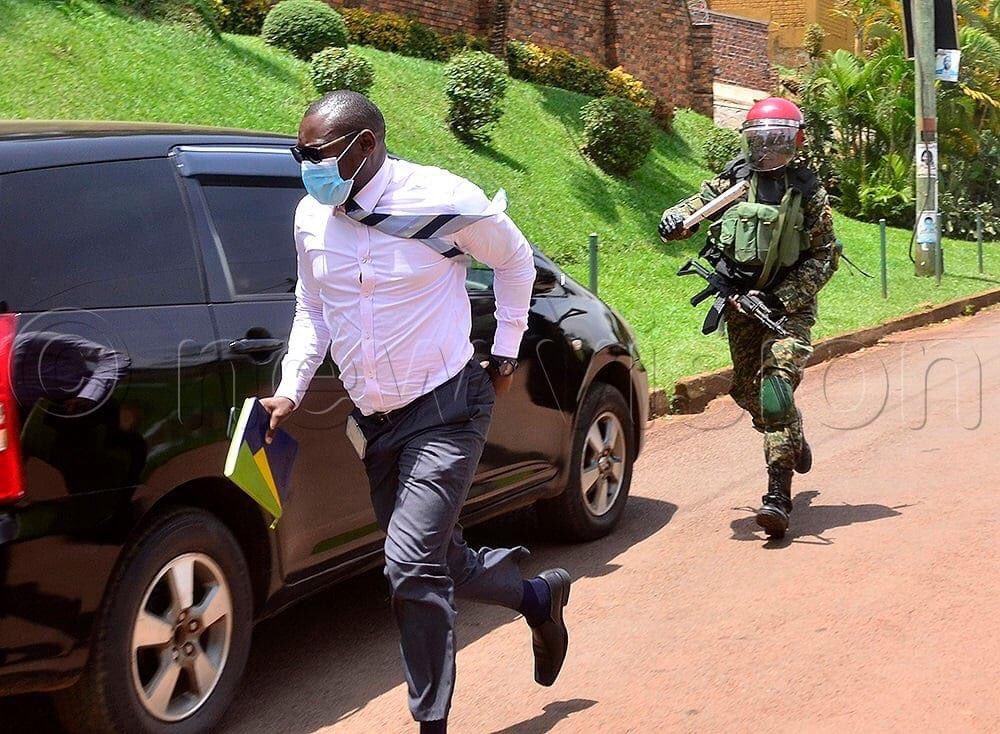

During the melee, which many have described as “despicable”, journalists Timothy Murungi (deputy photo editor of New Vision), Henry Sekanjako (senior New Vision reporter), John Cliff Wamala (reporter with NTV-Uganda), Joseph Sabiti (senior reporter with NBS), Irene Abalo (reporter with Daily Monitor) and Amina Nalule of Galaxy radio were beaten by the military police.

Badly injured, some returned to work stations in wheel chairs or clutches. In one of the photos, which has since gone viral, Sekanjako is seen taking off Olympic style from the blood thirsty armed military security officers.

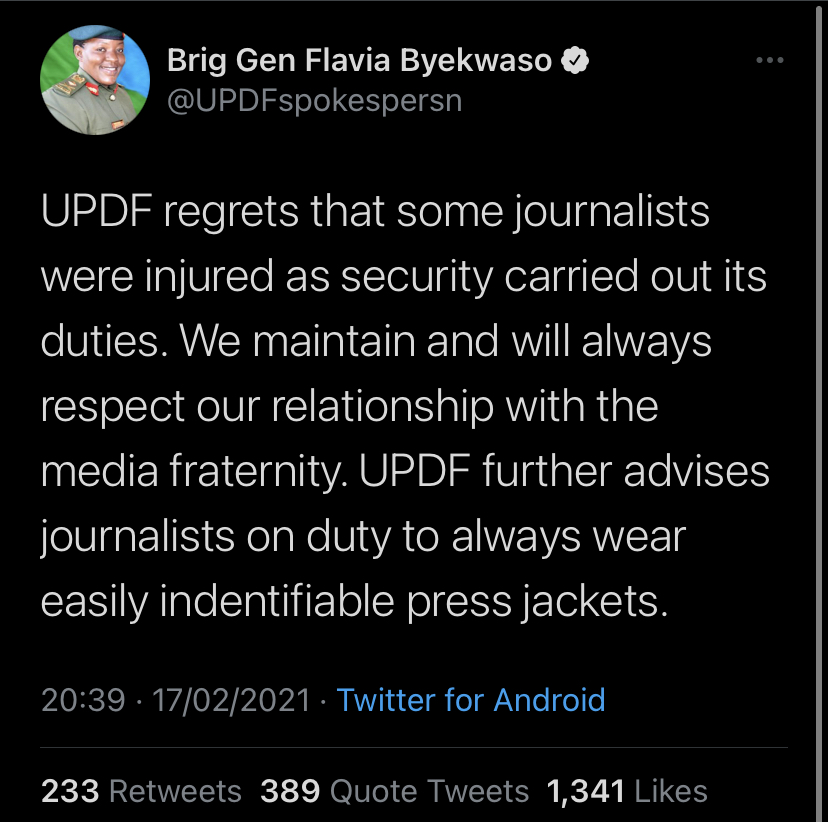

Commenting about the scuffle, the spokesperson of the Uganda People’s Defence Forces (UPDF), Brig. Flavia Byekwaso, advised scribes on duty to always wear “easily identifiable press jackets”, if they are to be spared the wrath of security.

“UPDF regrets that some journalists were inured as security carried out its duties. We maintain and will always respect our relationship with the media fraternity. UPDF further advises journalists on duty to always wear easily identifiable press jackets,” Byekwaso said, adding that only three people, including Bobi Wine, were cleared to access the United Nations Human Rights office in Kololo, Kampala, and the subsequent deployment was designed to deter processions and prevent the spread of COVID-19.

“The group assaulted one of the security personnel at the cutoff point and that required they be pushed back forcefully: Hence the scuffle. Therefore, it is not correct to allege that journalists were targeted,” Byekwaso added.

Going forward, the Chief of Defence Forces (CDF), Gen. David Muhoozi, added that journalists should at all times be visibly identifiable during the execution of duty in order to avoid crossing the line.

So, why do you employ force on unarmed citizens? Why beat people rather than explaining to them? Why injure or strike to maim messengers executing their duty instead of protecting them?

So, if journalists were clearly identifiable, does this justify the beating of other citizens who are not journalists?

These are the evolving questions from the February 17 scuffle between journalists and security.

Yet despite the emerging trend, as one journalists remarked; “the nasty story of security forces assaulting journalists and violating press freedom rarely gets prominence” in the media.

Helpless and placed within the jaws of a brutal security system on one hand and a capitalistic media empire on the other, some journalists have resorted to prayer—crying to God to prevail over those that are all out to undermine the noble profession.

Which way for press freedom?

Whichever way you dissect the November 18 and February 17 Bobi Wine events, the central theme that runs through the analysis is the fact that there is an attack on media and Article 29 of the Constitution of Uganda.

Freedom of expression is the right to seek, receive and impart information. Generally, freedom of expression entails the freedom to hold opinions. To seek, receive and impart information of all kinds, either orally, in writing, in print, in form of art, gestures, effigy, cartoons, monuments and any other chosen media without interference by public authority (See: International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights), (Article 19) and the (European Convention on Human Rights, Article 10).

In fact, the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights puts it better in Article 9

- Every individual shall have the right to receive information.

- Every individual shall have the right to express and disseminate his opinions within the law.

Perhaps Nazi Germany Pastor Martin Niemoller stressed freedom of expression more vividly: “First, they came for the Communists and I did not speak up because I was not a Communist. Then they came for the Jews and I did not speak up because I was not a Jew. Then they came for trade unionists and I did not speak up because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for the Catholics and I did not speak up because I was not a Catholic. Then they came for me and by that time there was no one left to speak for me.”

And like Lord Denning said in Schering Chemicals v Falkman Ltd (1981) 2 W.L.R 848, freedom of the press “Covers not only the right of the press to impart information of general interest or concern but also the right of the public to receive it.”

In Thomson Newspapers Co. v Canada (1998) 51 CRR 189, the Supreme Court emphasized that freedom of expression has four broad special objectives to serve:

- It helps an individual to obtain self-fulfillment.

- It assists in discovery of truth and in promoting political and social participation.

- It strengthens the capacity of an individual to participate in decision-making.

- It provides a mechanism by which it would be possible to establish a reasonable balance between stability and change.

Article 29 of the Constitution states that: “Every person shall have the right to and freedom of conscience, expression, movement, religion, assembly and association.”

In Charles Onyango Obbo & Another v AG, a case concerning freedom of expression, the Supreme Court of Uganda, stated that protection of guaranteed rights is a primary objective of the Constitution. Court added that limiting the enjoyment of freedom of expression, among other rights, is a secondary objective.

“It’s difficult to imagine a guaranteed right more important to democratic society than freedom of expression. Indeed, a democracy cannot exist without that freedom to express new ideas and to put forward opinions about the functioning of the public institutions,” Justice Joseph Mulenga, said, citing the Canadian case of R v Oakes where the Canadian Supreme Court held that any limitation of freedom of expression must justified.

In Uganda, the test and standard of a justifiable limitation of freedom of expression is enshrined under Article 43 (2) of the Constitution.

“Democratic values and principles are the criteria on which any limitation on the enjoyment of rights and freedom guaranteed under the Constitution has to be justified,” the late Justice Mulenga, a celebrated media freedom trailblazer, held in the Charles Onyango Obbo case, a court decision, which journalists say, de-criminalised the publication of false news.

Yet despite the legal protection, the State continues to raid media houses, impose subtle bullying of media owners, arm twist media practitioners, threaten financial and political sanctions to ‘unfriendly’ media operators and also clobber journalists in broad-day light.

Confronting the internet

Freedom of expression on the internet, a booming new avenue for many Ugandans to air out their views, and also amplify citizen journalism, is also being targeted. Some attacks have come in the form of the tag-line ‘fake news’.

The regulation of internet use is particularly provided for under Section 4 of the Uganda Communications Commission Act, 2013.

Under the above provision, UCC can block a website used for hate speech, but the provision has been used to abuse freedom of expression by overzealous government officials.

For example, in the post 2016 general election period, government shut down social media access to Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter and other digital channels in the country.

To many journalists and youth, this was a big affront to freedom of expression.

Criminalising and curtailing internet use the China-style, from a media perspective, has a chilling effect on freedom of expression, especially at a time when Ugandan media is testing the efficacy of digital solutions to market their products to 78% of the country’s youthful population that lives and thinks internet and social media.

The build-up to the onslaught on internet and social media use started in 2003 with the blocking of Uganda Radio Katwe, search for Tom Voltaire Okwalinga (TVO), the closure of CBS radio, Radio Ssubi and Akabozi Kubili in 2009 during the Buganda riots, and the ban on live talk shows dubbed ‘ebimeza’ and live video picture shows called ‘ebimansulo’.

In this “nation”, regime apologists argue, a reputation can be destroyed in an instant through a drunken post, an anonymous email or a “trigger-happy” Tweet.

Facebook pages like the now infamous TVO, Stella Nyanzi, Radio Katwe are popular for speaking out boldly about injustice, a move that government and certain powerful individuals dislike.

In fact, to curtail the emergence of the Edward Snowden and Julian Assange-like personalities in Uganda, some lawyers have shockingly filed cases to fight anonymous bloggers, whose content on social media, in their view, is unpalatable.

For instance in Fred Muwema v Facebook Ireland Limited, Facebook declined to remove a post that Muwema, a Ugandan lawyer, considered defamatory.

Within the media circles, Muwema’s law suit was viewed as an affront to freedom of expression, even though Section 179 of the Penal Code Act creates the offence of criminal libel.

The provision states: Any person who, by print, writing, painting, effigy or by any means otherwise than solely by gestures, spoken words or other sounds, unlawfully publishes any defamatory matter concerning another person, with intent to defame that other person, commits the misdemeanor termed libel.

Journalists attempted to challenge the above provision in the Joachim Buwembo v AG case, but court declined to strike it out.

On the good side, the Constitutional Court in Andrew Mwenda and Anor V AG, outlawed the offence of sedition, which the State used to deploy to curtail freedom of expression, but declined to strike out the offence of promoting sectarianism and defamation.

Yet the likes of Muwema and government agents continue to use the above provisions to curtail media freedom. This inevitably has a chilling effect on on-line and media freedom of expression.

In the Kenyan case of Robert Alai v Attorney-General, Robert Alai, a prominent social media personality and blogger, had posted on Twitter regarding President Uhuru of Kenya that: “Insulting Raila is what Uhuru can do. He hasn’t realised the value of the Presidency. Adolescent President. This seat needs maturity.”

He was charged with undermining the authority of a public official under section 132 of the Kenyan Penal Code. He sought a declaration that section 132 was unconstitutional.

The Court, relying on article 33 of the Kenyan Constitution which guarantees freedom of expression, noted that people ‘cannot be freely expressing themselves if they do not criticise or comment about their leaders and public officers’.

A similar ruling was recently issued by Court in Uganda, in the Stella Nyanzi v Uganda case where she was accused of ‘cyber-harassing’ of President Museveni and his late mother, Esteri using her social media Facebook page.

Nyanzi was charged under the Computer Misuse Act, a relatively new law that ranks with the Regulation of Interception of Communication Act (phone-tapping law) and the Anti-Pornography Act (mini-skirt law), as ‘real threats’ to freedom of expression.

These laws are a danger to the right to privacy as enshrined under Article 27 of the Constitution in so far as spying, regular surveillance, interfering with personal property, entry into private premises and phone tapping is concerned.

In the case of Victor Juliet Mukasa and Others v AG, agents of the State broke into the residences of the plaintiffs in such for material of suspected lesbians. They confiscated some property of the applicants such as compact disks and correspondence. Court held that the actions of the state were in breach of the right to privacy.

The trespass by the State was also felt within media circles in 2013 when Daily Monitor and Red Pepper offices were raided, searched, and thereafter closed for over two months, following the publication of a letter authored by the ex-coordinator of intelligence services, Gen. David Tinyefunza aka Ssejusa on the ‘Muhoozi project’, detailing how President Yoweri Museveni is preparing his son, Lt. Gen. Muhoozi Kainerugaba, to succeed him.

In a related event, the Parliamentary Commission in 2013 banned two journalists from reporting at Parliament following their publication of probing articles on the bad blood between Speaker Rebecca Kadaga and her deputy Jacob Oulanyah.

In the case of Sulaiman Kakaire and David Lumu v The Parliamentary Commission, the two journalists that were expelled from Parliament, challenged the Speaker’s directive and Court quashed it.

However, this ruling did not deter Parliament from the continued interference with freedom of expression. In 2016, Parliament ejected journalists without degrees, and issued new press accreditation rules limiting covering of Parliamentary proceedings to journalists who hold degrees only.

In subsequent directives, in 2017, the Speaker also wrote to media houses, requesting them to send ‘fresh’ journalists for accreditation to cover parliament, a move that jettisoned out experienced reporters/journalists, who are more grounded to cover the events.

The COVID-19 effect

However, in my view, the story of the media in Uganda is that of resilience.

When our readership dropped, and our advertisers’ knees softened like jelly, the newsroom bean counters were quick to sort the whiff from the chuff. Out went the journalists found excess to requirements; in came pay cuts, forced leave without pay, and restructuring.

Kampala’s worst kept secret is that a journalist’s pay cheque is hardly ever worth the ink used to print it.

Journalists were already struggling to put three solid meals on the family dining table before COVID-19. But now here they were, fulfilling the Biblical premonition that “for those who have little, even the little shall be taken away from them.”

COVID-19 has officiated the new journalism age, where journalists from the bygone era have to adapt and become acquainted with interviews on Zoom, filing stories in your bedroom, reporting for radio, TV and the newspaper if they are to survive.

Few things highlight the perceived value of the media as the security forces’ early treatment of the media after the government announced the full lockdown. Members of the Local Defence Units beat up, detained and blocked journalists from movement because they did not consider the media an essential service.

Even when the police leadership clarified this, media freedom civil society organizations continued to report cases of members of the security forces beating journalists, compounding the hazardous nature of media practice in Uganda that had made carrying a recorder and camera a ticket to a beating.

When journalists retire home at the end of the day, they do not just pack into a garage and rest their pistons until the next day. They retire to families that require nutritious meals just like bankers’ children. And in the COVID-19 special season, many journalists have simply not had the luxury to retire home with the bacon.

Yet in the end, no scathing laws can take away the right to express views freely—the freedom, Cassin. R says, “No one has the power to control his internal thoughts and feelings or to prevent him (or her) from outwardly expressing his (or her) thoughts and feelings.”

Mr. Lumu is a senior journalist with the New Vision and lawyer.