By Tundu AM Lissu

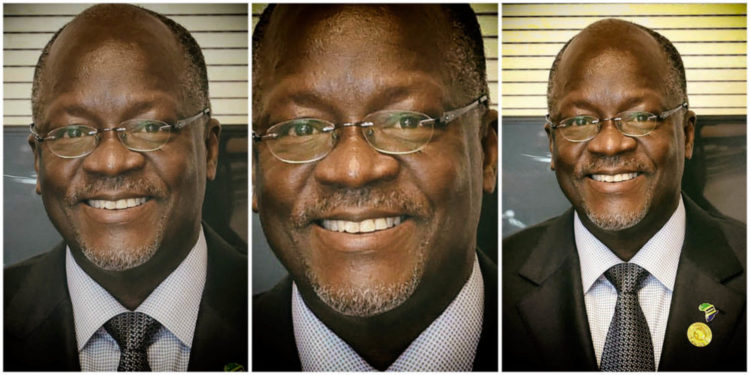

John Pombe Magufuli, the fifth president of the United Republic of Tanzania, died this past week. He was 61 years old. Known to friends and foes alike by a welter of nicknames — with “Tinga tinga” (Bulldozer) or simply “Magu” beloved of his many supporters; and “Jiwe” (Stone) or “Magufool” the favourites of his equally numerous detractors — president Magufuli was a controversial and divisive figure in life. He has died an equally controversial death and, I dare say, the legacy of his brief presidency will be just as controversial.

For starters, the cause and actual date of his death are bitterly contested. Announcing his death on the evening of Wednesday, 17 March 2021, then vice president and now President Samia Suluhu Hassan told the nation and the world that Magufuli had died earlier that evening of complications brought on by a long-standing heart condition. Soon enough, an undated and untitled newspaper clip, but most likely from the government-owned newspaper The Daily News, started circulating on social media showing that a much younger-looking “John Pombe”, a postgraduate student at the University of Dar es Salaam, “has been suffering from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy” and was “required to undergo surgery in Britain”.

Although the newspaper clip is undated, this must have been between 1992 and 1994, while Magufuli was studying at the University of Dar es Salaam for his Master of Science degree programme. It lent credence to the new President Suluh Hassan’s claim that he died of chronic atrial fibrillation (abnormal heart rhythm). However, many — myself the foremost — believe the president, an unreconstructed Covid-19 denier, died much earlier and the underlying cause of his death was Covid-19 complications.

I was the first to break the news that something strange was going on with Magufuli’s health. Following tips from credible sources in the United States and South Africa three days earlier, on 7 March, a Sunday, I tweeted that the president had not been seen in church that day, an unusual event for a president, whose weekly church attendances were the subject of live television coverage and an obligatory front-page story in all the major newspapers, both government-owned and privately held.

I observed in that tweet that the president had not attended the East African Community Heads of State Summit held virtually the previous week either; and that, indeed, he had not been seen in public for over a week, another highly unusual occurrence. I asked the chief government spokesman to tell the nation where the president was and whether he was in good health.

As an unabashed dinosaur in all matters of modern information technologies, I am not a card-carrying member of the Twitterati. But, in the days preceding the official announcement of Magufuli’s death on 17 March, I produced a steady stream of tweets about the unfolding drama of a missing president. In the 10 days between that first tweet and the official announcement of his death, I tweeted 26 times, eliciting nearly 10 million “impressions”. For the most part, the government of Tanzania kept a stony silence. So did the local print and broadcast media, cowed by five years of brutal repression by the Magufuli regime.

But as news of the president’s illness and rumoured hospitalisation in Nairobi, Kenya, exploded in the media, the government finally buckled under the pressure of an unaccustomed international media glare. During Friday prayers in the southern Highlands town of Njombe on 12 March, Prime Minister Kassim Majaliwa flatly dismissed the reports of the president’s illness and hospitalisation, attributing them to the hatred and envy of “Tanzanians who have fled the country”.

Three days later, however, then vice president Suluhu Hassan dropped the broadest hint yet that the president could actually be in hospital. Without naming any names, and without being prompted, she declared that it was not unusual for people to be checked for flu or fevers or any other illness.

Nevertheless, by this time photographs of tarp-covered military vehicles carrying biers and a military band practising martial music were furiously circulating on social media. Without any credible media strategy, the government resorted to its time-tested methods of silencing the unruly media: threats, intimidation and arrests. Justice Minister Mwigulu Nchemba’s threats on 11 March that anyone spreading rumours of the president’s illness would be prosecuted under the country’s penal and cybercrime laws was followed by a spate of arrests of social media users countrywide.

And then came Hassan’s announcement on 17 March that the president had died of heart complications that had allegedly first started on 6 March, that he had been suffering from heart problems for more than 10 years and had indeed been twice hospitalised in Dar es Salaam in the past 10 days. After days of intense media and political drama, the announcement of his death was greeted with shocked resignation by his supporters; and relief, if not jubilation, by his many opponents and detractors. As his most persistent critic and perhaps his most prominent victim, I was and I am, frankly, relieved to see him go.

John Pombe Magufuli was an accidental president. With the governing party Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) bitterly divided in the run-up to the 2015 general elections, Magufuli was nominated to face former premier and CCM heavyweight Edward Lowassa, who had recently joined the main opposition party Chadema, and was to become the standard bearer for the opposition coalition UKAWA. Even though he was a senior cabinet minister for more than a decade, having been in the Cabinet since president Ben Mkapa’s first term in the mid-1990s, Magufuli was considered anything but a CCM insider or power broker.

But in a CCM tainted by widespread allegations of high-level corruption, and with the spectre of the ascendant opposition, his outsider status became a boon and he was nominated to be the CCM presidential candidate. After a bitterly fought contest with Lowassa, Magufuli was elected president with 58% of the vote, the lowest of any previous CCM presidential candidate.

As president, Magufuli took the country, and the outside world, by storm. In his first few months in office, he was everywhere, hiring and firing on the go and making all kinds of on-the-spot decisions, big and small. There were no sacred cows as he sacked and publicly humiliated the high and mighty of the Kikwete and Mkapa years.

There was no law either, as he hired civil servants, political hacks and others he was not legally entitled to hire; and terminated from public service persons he was not legally empowered to remove. No civil servant was safe under Magufuli as he chopped and hacked at will. In the process, he became the employer-in-chief as well as the ultimate disciplinary authority for all public employees and, above him, there was no court of appeal or any other recourse for justice.

One of Magufuli’s early targets was the private sector, both local and foreign, which had thrived under the business-friendly policies of the Kikwete and Mkapa administrations. Using the fight against corruption as a smokescreen, he launched a massive attack on the business community, using ad hoc task forces comprising tax officials and personnel from the anti-corruption bureau, police, intelligence and security services and the military. These task forces scoured the local banks looking for financial records of businesspeople with substantial cash reserves and other valuable assets.

These assets were seized, invariably without court orders, and their owners threatened with or actually arrested and charged with a bewildering array of economic “high crimes and misdemeanours”, all of them without bail and carrying stiff penalties. Those who resisted were often dramatically kidnapped at gunpoint and disappeared for days, before being released apparently unharmed. None of these kidnappings has ever been investigated or resolved. No one has been arrested or charged. Nor has the government and its law enforcement agencies ever given a satisfactory explanation for this wave of kidnappings and disappearances of prominent business people.

The war against corruption soon morphed into an “economic war” against foreign investors and foreign businesses, particularly in the mining and other extractive sectors of the economy. Here, too, assets were seized and company executives arrested and charged with serious economic crimes such as tax evasion and money-laundering. As with local businesspeople, foreign investors too were blackmailed into parting with substantial sums of money or assets at the pain of endless detention in terrible conditions in the country’s overcrowded prisons and police cells.

Covid testing, publication and data-sharing with WHO was discontinued by 19 April 2020. And any dissemination of Covid-related information was criminalised under Tanzania’s draconian cybercrime laws.

Magufuli has been widely hailed for his successes in this fraudulent “war on corruption”. In reality, this “economic war” was a Mafia-style shakedown on a gigantic scale, organised and managed from the Magufuli State House. Its targets were anyone who could be fleeced, ranging from cashew nut peasant farmers in the southern regions to foreign exchange dealers in Dar es Salaam and other major cities to multinational mining companies.

Magufuli’s primary target had always been democracy, particularly the democratic opposition led by Chadema. In a nationally televised address on the 39th anniversary of CCM on 6 February 2016, he openly and bluntly promised to put an end to the opposition parties by the 2020 general elections.

What happened next was captured by Dan Paget, the University of Aberdeen politics professor, in the following terms: “… [T]here has been a sea-change since 2015 when Magufuli came to power. Things that were permitted in 2014 are not permitted today. The media are censored. Political parties are oppressed. Politicians and civic activists are harassed in court, and out of it. Rallies were banned for four years. There has been a spate of violence by anonymous actors… connected to the state”.

It was in this environment that I was nearly assassinated on 7 September 2017, some two hours after Magufuli had declared, on national television, that those who opposed his economic war “[did] not deserve to survive”. It was also in this climate of political repression that many Chadema leaders and political activists; journalists and social media bloggers; artists and businessmen; human rights activists, or simple peasants and fishermen in and around the country’s sprawling protected areas, were either murdered, kidnapped, or disappeared. Many were tortured in police cells or in secret locations operated by the intelligence and security services or charged in courts of law with economic offences, the most preferred being money laundering.

The true death toll of this state-orchestrated lawlessness may never be known, given the level of impunity which characterised the Magufuli regime. It must, however, number in the many hundreds at the very least. This was in a country that has never witnessed any of the civil and political strife characteristic of the region for decades past. Idi Amin Dada, Jean-Bédel Bokassa, Francisco Macías Nguema, Mengistu Haile Mariam and other bloodthirsty tyrants of Africa’s post-colonial past were all soldiers who came to power through bloody military coups. As a consequence, these military dictators maintained themselves in power through violence.

Magufuli came to power through democratic elections. He then turned on the democracy that brought him to power and tried to destroy it and his political opponents and rivals through state violence and bloody purges. Having been part of the CCM governments for the previous two decades, he can rightly be said to have been part of the problem that he now wished to violently solve. Without any excuse, legitimate or otherwise, he had to manufacture an “economic war” against unnamed foreign enemies in order to justify his bloody war on democracy.

After three years’ living abroad and recovering from the deadly consequences of the 7 September assassination attempt, on 27 July 2020 I returned to Tanzania to face my old tormentor in the general elections slated for 28 October. Tanzania Elections Watch (TEW), an election observation initiative of several civil society organisations in Eastern and Central Africa, described the elections as “… one of the most competitive in the history of multiparty politics in Tanzania”.

The general elections proved anti-climactic. In an interview given shortly after the results of the elections were declared, Paget pointed out that the National Electoral Commission not only declared the defeat of the opposition’s most admired leaders in their biggest strongholds, “these defeats [we]re by astounding margins”. Dr Paget elaborated further that what puts the results of these elections over the top is that “… the ruling party’s victories have been declared in places you would least expect them to win, and at a scale which is hard to believe”.

This was also the conclusion of Sina Schlimmer and Cyrielle Maingraud-Martinaud of the French Institute for International Relations, who wrote in a perceptive article also published shortly after the results were announced: “Even though the declaration of CCM’s victory was expected, the result lacks credibility, and the level of irregularities, violence and electoral manipulation estimated by experts and observers have led to international consternation and concern about Tanzania’s political trajectory.”

The US government, through the State Department’s Bureau of African Affairs, agreed: “… The election was marred by widespread irregularities and was the culmination of years of systematic intimidation and marginalisation of the opposition parties, civil society organisations and independent media.”

So did the TEW, chaired by Professor Frederick Ssempebwa, formerly chairman of the Uganda Constitutional Review Commission, which denounced the general elections as “not free; not fair”. TEW concluded that the elections marked “a significant regression of democracy in the country’s democratic development”.

Nevertheless, Magufuli was sworn in and started his second term as president. Soon there were open calls, inside the now largely CCM parliament and outside of it, that Tanzania’s constitution be amended to remove presidential term limits, in place since 1984, in order to allow him to rule for life if needed.

And then the second wave of the coronavirus struck and the pandemic rapidly spread across the country.

The first Covid-19 case in Tanzania had been diagnosed in March of 2020. At first, Magufuli’s approach to the pandemic was consistent with the measures recommended by the World Health Organisation and reflected the global scientific consensus. But as the death toll began to rise and the true political and economic ramifications of the pandemic and the scientific measures proposed to combat it became clearer, Magufuli changed tack.

Covid testing, publication and data-sharing with WHO was discontinued by 19 April 2020. And any dissemination of Covid-related information was criminalised under Tanzania’s draconian cybercrime laws.

Soon, this PhD in chemistry decreed three days of national prayers to chase away the “satanic” coronavirus. He sent his foreign minister to Madagascar to fetch a planeload of herbal potions to fight the disease, and actively encouraged the use of a bewildering array of locally made steam inhalations, herbal concoctions and prayers to defeat the pandemic. Soon thereafter, he declared Covid-19 defeated and was even given an award by evangelical Christian bishops, his loudest cheerleaders, for leading the nation to victory through divine intervention, rather than relying on the hated, godless, Western science and the global corporate Illuminati behind it.

But the coronavirus refused to be tamed. The dreaded second, more virulent, wave soon caught up with Tanzania. And it hit the elites within and outside the Magufuli government particularly hard. Senior government officials and cabinet ministers, former and current, were felled by Covid-19 one after the next. Army generals and senior clerics; prominent academics and business leaders; senior bureaucrats and professionals of all cadres, were all affected. In one day, 17 February, ambassador John Kijazi, Magufuli’s own chief secretary and head of the civil service; and the First Vice-President of Zanzibar, Maalim Seif Sharif Hamad — considered to the father of the modern Zanzibari nationalist movement and of the Tanzanian democracy — died of Covid-19.

On 12 March I tweeted a picture of Magufuli swearing in the former foreign minister, Dr Augustine Mahiga, whose much-publicised Covid-19 death a year earlier had most likely prompted Magufuli to ban the testing and publication of any Covid-related information. In the picture was Kijazi and another close aide who had also recently died of Covid-19. The noose was rapidly tightening around the neck of the visibly shaken and tired-looking president. His last appearance was on the 27 February swearing-in of Dr Bashiru Ali, the then CCM secretary-general, to be his new chief secretary.

Tanzania’s mainstream media had all through this period kept a deathly silence, on account of which I tweeted on 14 March: “It is a telling indictment, not just of our so-called press, but of the Magufuli dictatorship, that the biggest news story of all time, the disappearance and rumoured demise of the president, is a top story in Kenya and worldwide but in Tanzania it is as if nothing has happened!”

Karma finally caught up with him. On 10 March, three days after my initial tweet, I tweeted the following: “It is a sad comment on his stewardship of our country that it has come to this: that he himself had to get Covid-19 and be flown out to Kenya in order to prove that prayers, steam inhalations and other unproven herbal concoctions he has championed are no protection against the coronavirus.”

Based on information of his imminent death I was receiving from my Kenyan and Tanzanian sources, that same day, I tweeted again: “The latest update from Nairobi: “They are planning to sneak him out to India to avoid social media embarrassment from Kenyans. They feel that it will be more embarrassing if the worst happened in Kenya. The most powerful man in Tanzania is now being sneaked about like an outlaw!”

The next day, 11 March, I received information from my Kenyan sources that he had indeed been “snuck out”. I tweeted: “Latest update from Nairobi: The man Who Declared Victory Over Corona ‘was transferred to India this afternoon.’ Kenyans don’t want the embarrassment ‘if the worst happens in Kenya.’ His Covid denialism in tatters, his prayer-over-science folly has turned into a deadly boomerang!” By the time Hassan finally declared him officially dead, I already had reliable information that Magufuli had been dead since 10 March, the day he was snuck out of Nairobi.

Tanzania’s mainstream media had all through this period kept a deathly silence, on account of which I tweeted on 14 March: “It is a telling indictment, not just of our so-called press, but of the Magufuli dictatorship, that the biggest news story of all time, the disappearance and rumoured demise of the president, is a top story in Kenya and worldwide but in Tanzania it is as if nothing has happened!”

The evening before I had promised, quoting Mark Twain, the great American humourist, that, although I did not wish anyone dead, “I will write, not merely read, a certain obituary with great satisfaction!”

I have now delivered on that promise. I hope it does justice to the man who held Tanzania by the neck, in a vice-like grip, for five painfully long years. Africa did not mourn the passing of Idi Amin, Bokassa, Nguema, Mobutu Sese Seko or, more recently, Robert Mugabe. It should not be mourning this vicious tyrant who, with crude anti-imperialist phrase-mongering, masqueraded as a great African patriot, while terrorising his countrymen and women and looting the country’s treasury in order to transform his lakeside village of Chato into Tanzania’s Gbadolite.

Instead, his brief but damaging rise and stay in power should serve as a precautionary tale of the mortal danger presented by power-hungry demagogues who come with pretty phrases and solemn promises that they care for the interests of the common people against purported, mostly manufactured, foreign enemies. DM

This article was first published by Daily Maverick.