BY ROBERT MADOI

After holding him incommunicado for nearly a week, the Uganda Police Force used the first workweek of 2022 to confirm the incarceration of Kakwenza Rukirabashaija. The writer, who was to great acclaim named International Writer of Courage last October by 2021’s PEN Pinter winner, has carved a reputation of being a straight talker who uses humour and rumour with varying degrees of success both online and offline.

Rukirabashaija’s deployment of allegories in his past bodies of work did not insulate him from running into trouble. He was twice remanded in custody in 2020. During his speech after accepting to share the 2021 PEN Pinter Prize with Zimbabwean writer and activist Tsitsi Dangarembga, Rukirabashaija said thus: “When I was hanging on chains in the dungeons, I swore to my tormentors that I would never write again if they gave me a chance to live—as if they were some deities or God. Truth is, I survived death.”

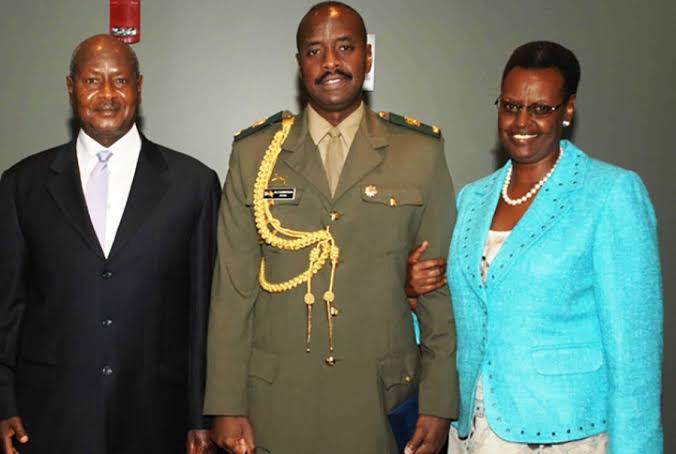

The PEN accolade emboldened Rukirabashaija, and at the backend of last December 2021 he posted tweets that were deemed to have attacked the person of President Museveni and his son, Lt Gen Muhoozi Kainerugaba. Charles Twine, the spokesperson of the police’s Criminal Investigations Directorate, said the tweets were “derogatory” in nature and posted “without any purpose of communication.” A “civilised person” would, Twine added, find the tweets distasteful.

Uganda—much like many African countries with strong oral traditions—has a complicated history of using political humour and rumour to force rulers who are usually economical with information to dialogue with the ruled. The likes of Stella Nyanzi and Rukirabashaija have come to embody an ‘unruly public’ whose parodic and satirical language—even dark humour—has turned online spaces into grotesque symposiums. Their lived experiences are representative of the trap and opportunity tucked in digital activism. This cocktail of peril and promise came out quite starkly last year. Never has the temptation to see a win as a sign of the times ever been so overbearing than when Maria Ressa, the chief executive and co-founder of Rappler, and Dmitry Muratov, the editor-in-chief of Novaya Gazeta, were named 2021’s laureates.

The Norwegian Nobel committee recognised the journalists for their “efforts to safeguard freedom of expression.” The committee’s chair, Berit Reiss-Andersen described freedom of expression as “a precondition for democracy and lasting peace”, but hastened to add — with awful irrevocable certainty — that “democracy and freedom of the press face increasingly adverse conditions.”

Ressa, whose news organisation—started as a Facebook page in 2011—has gone on to face multiple criminal charges for holding Philippines President Rodrigo Dueterte accountable, wrote that the recognition was “hopefully [an indication] of how we’re going to win the battle for truth. The battle for facts. We hold the line.”

Free speech in retreat

Unfortunately, freedom of expression has been in retreat so much so that it finds itself falling foul of the line between success and failure. The think-tank, Freedom House for instance discovered that 30 of the 70 countries it dedicates itself to monitoring brought in tougher curbs on free expression online in 2021. The steepest declines in Internet freedom were in Myanmar (-14) as well as Belarus (-7) and Uganda (-7). In the annual study titled ‘Freedom on the Net’, Freedom House noted that the Ugandan government found itself stronger than ever in the conviction that online spaces ought to be policed because of the 2021 general elections.

The report read thus: “Throughout the electoral period, a network of pro-government social media accounts flooded the online environment with manipulated information, while online journalists covering the campaign of opposition candidate Robert Kyagulanyi, better known as Bobi Wine, faced harassment and physical violence.”

The days before and after the poll did not pass easily for people in Uganda. On the eve of the poll, the Uganda Communication Commission ordered Internet Service Providers to suspend the operation of Internet Gateways. The complete Internet blackout spanned nearly 100 hours, with access only restored on 18 January after President Museveni’s win (by 59 percentage points to Bobi Wine’s 34) had been cast in stone.

As an army of young people strive to find their political voice on digital spaces, autocrats have found novel ways to stifle free expression online. In its 2021 report, Freedom House grimly noted that “the rights of Internet users have become the main casualties…in [this] high-stakes battle.” The 2021 Ugandan general election underscored this deepening repression around electoral activities, which is more frequently pernicious in its consequences.

Uganda, whose most recent census in 2014 puts its citizens aged between 10 and 24 at slightly above 12 million, prepared to go to the polls in January of 2021 with the so-called youth vote central to the fortunes of contestants. The young voters, who rattled along with terrific energy in various online spaces, were largely expected to rally behind Bobi Wine. The young pretender was having his first crack at the Ugandan presidency, and succeeded in creating a chaotic mix of peril and promise using digital tools.

Internet freedom takes nosedive

While some of the results that Bobi Wine enjoyed were stunning, his effort in a pandemic-riddled electioneering period sputtered along without conclusion. His party—National Unity Platform—would later claim that part of the reason for this outcome was the climate of fear, repression, and apprehension President Museveni created around both offline and online conversations. The party’s spokesperson, Joel Ssenyonyi said the repressive campaign was “because they know that we are putting together evidence to show the world how much of a fraudster Museveni is.”

Freedom House’s 2021 findings—which indicate that “global Internet freedom declined for the 11th consecutive year”—offer considerable support. They show how online speech has been affronted to a unique degree, with spyware like NSO Group’s Pegasus proliferating.

The iPhones of as many as 11 US Embassy employees based in Uganda are believed to have been hacked thanks to the spyware.

The use of Internet shutdowns threatens to remain in vogue. In 2020, twenty-nine countries shared 155 such shutdowns in a bid to—among other things—stymie critics. In Uganda, online critics who constitute a growing unruly public have the threat of reprisals always hovering menacingly above their heads. The government has used a string of draconian laws (Regulation of Interception of Communication Act, 2010; Computer Misuse Act, 2011; Anti-Terrorism Act, 2002, National Information Technology Authority, Uganda Act, 2009; Electronic Signatures Act, 2011; Electronic Transactions Act, 2011; Uganda Communications Act, 2013) to create chilling effects amongst people entrusted to its care.

Whilst toasting to Ressa and Muratov’s feat, Reporters Without Borders called the award “a call for mobilisation to defend journalism” that created a cocktail of “joy and urgency.” The press freedom NGO’s most recent index on free speech is damning in the assessment that the vast bulk (73 per cent) of the 180 countries it evaluates are in a “difficult or very serious” space. These are indeed tough times for free speech, both offline and online.

Robet Madoi is a senior journalist, editor and academic based in Kampala.