It’s 9am and Rosette Kamuntu is at home in Ntinda preparing a snack after dropping her kids to school. She starts feeling abdominal pain. She thought it was a simple pain that would easily go away by self-medicating. She took Flagyl tablets that treat intestinal infections. But at around 7pm, the pain intensified and she rushed to Life Link Hospital in Ntinda.

On diagnosis, it was an emergency case that needed to be handled urgently by a more sophisticated health facility. She had Ectopic pregnancy, a life threatening pregnancy which occurs when a fertilized egg grows outside a uterus.

The pain was too much and was supposed to be operated immediately. An ambulance was brought to take her to Mulago National Referral Hospital but on arrival, she was referred to Kawempe General Hospital, a new hospital that was upgraded five years ago to handle health care in obstetrics and Gynecology.

She was admitted at 11pm but spent the night with no help. A case that was supposed to be an emergency was not handled even on the following day.

At around 2pm on the following day, her relatives wanted her transferred to another hospital because they had failed to secure a bed in the theatre because of the overwhelming numbers of the mothers giving birth by Caesarean Section.

“We were told that there was a long queue of mothers giving birth. I was in too much pain. I thought I was not going to return home to see my kids,” she said.

After waiting for three more hours, her relatives were getting worried and decided to ask for a referral to take her to another hospital.

But the doctors refused, saying it’s the policy of government hospitals not to give referrals to go to a private facility.

“They said they could only let me out of the hospital only if I’m taken to Mulago Hospital where I went first before I was referred to Kawempe. I think the Mualgo people refused to admit me because they looked at me and thought I couldn’t not afford their charges. That’s why they referred me to Kawempe which is cheaper,” she says

As her relatives were still negotiating with the hospital authorities to allow them take her to another hospital, a midwife came and told them that she had finally secured a bed.

Kamuntu was wheeled to the theatre. But after 30 minutes, the midwife came back with bad news that they didn’t have an oxygen cylinder to be used in case Kamuntu’s oxygen levels went down during the operation.

Her brother was already pacing up and down in the hospital corridors. He had also called his friend doctors who had also advised him to take his sister out of the hospital and get a better health facility.

“My brother realized that the situation was getting out of hand. He had to lie to the doctors that he was going to take me to Mulago National Referral Hospital. They got an ambulance very first but I was taken to a private hospital,” she says.

Luckily, one of the doctors from Kawempe Hospital whom she doesn’t want to name escorted her in the ambulance along with her brother to a hospital in Nakasero, a Kampala suburb.

She was examined and within a few minutes was wheeled to the theatre and operated. But she started bleeding. The bleeding wasn’t severe but she was asked to pay shs300, 000 for blood.

“I thought blood was supposed to be free but at that time my relatives only wanted to see me recover and get out of the hospital,” she said.

Kamuntu’s case is shared by many poor mothers who have been unlucky not to leave the hospitals live because they can’t afford to buy blood.

The single mother of three was lucky that her brother could afford to buy the blood and save her life but Mary Olupo never survived.

She was a mother of two and on 20th October 2018, she went into labour expecting her third bundle of joy. The doctors took her to the theatre and delivered by C-section but when she was brought back in the evening, according to her former husband, Raphael Omony, she was unconscious and looked pale. “I asked one of the nurses why she was unconscious” he said.

But Umony was told that she would be okay. He hoped that she would resuscitate. However, a new doctor that came in the evening for the night shift, was shocked that Olupo had been in that condition without being given care.

The doctor ordered that she should be transferred to the Intensive Care Unit. When Olupo was taken to the Intensive Care Unit, Omony decided to rush and check on their two young children who had remained at home.

To his surprise, as he rode a boda boda, his sister-in who had remained at the hospital, called and told him that the nurses wanted shs200,000 for blood.

He rushed back to the hospital and found out that his wife had been taken to the theatre for another operation. By the time he reached, the relatives of Olupo gathered at the hospital. They had also paid the money.

On the following day, a nurse came and told Omony that they wanted more shs200,000. But Omony resisted to pay because he knew blood was supposed to be free.

After realizing that Omony was aware that blood is supposed to be free, the nurse changed the story and said it was a transport fee for someone to go and pick the blood.

In an interview with one of the national TV in 2019, Omony said the nurses were annoyed by his insistence not to pay the money.

“Later, some lady came with a bucket with a blood kit and spread the kit at the reception table and said ‘the blood is here but I’m hurrying for exams. Where is the money?’ I resisted for like five minutes but the lady started putting the blood back into the container,” he said.

Omony later budged and agreed to pay. He paid through Mobile Money and sent it to someone in the name of Kirabo. After sending the money, the nurses started the transfusion but it was too late and the situation worsened. She was referred to another hospital where she passed on two days later.

For Mr Noah Mulelo, a resident of Bulafa Village, Kigalama Parish, Namutumba Sub-county, he was asked to pay shs60, 000 but he didn’t have it and his wife passed on at Namutumba Health Centre III .

“I did not have the Shs60, 000 on me, and I am sure that if I had that money, my wife would not have passed on,” he said.

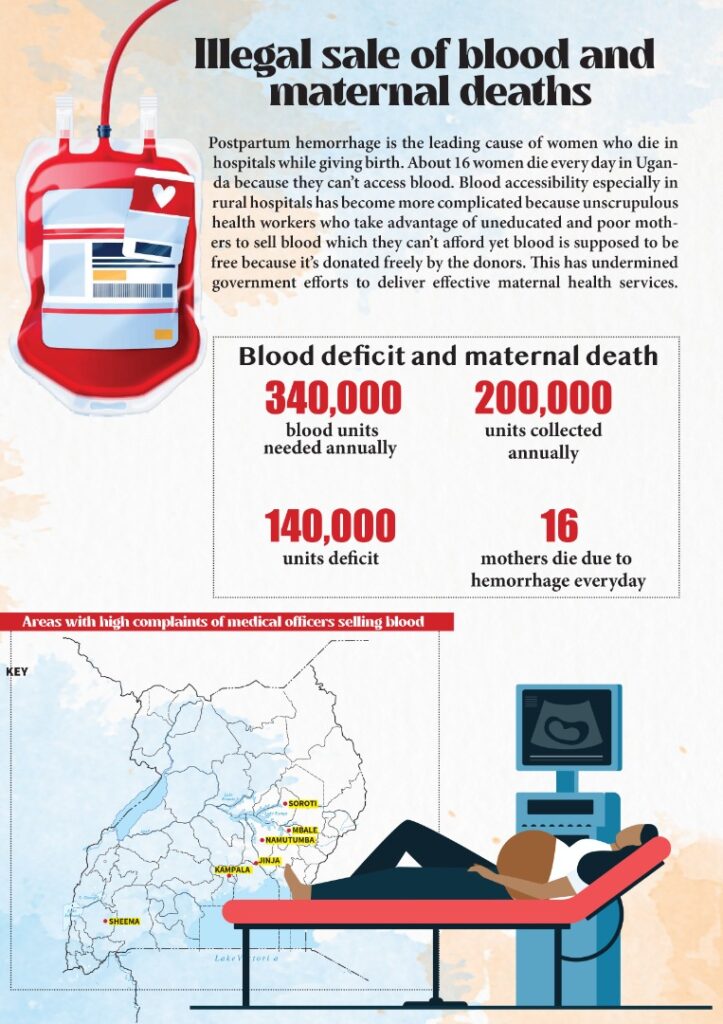

Postpartum hemorrhage is the leading cause of women who die in hospitals while giving birth. About 16 women die every day in Uganda because they can’t access blood. Blood accessibility especially in rural hospitals has become more complicated because unscrupulous health workers who take advantage of uneducated and poor mothers to sell blood which they can’t afford yet blood is supposed to be free because it’s donated freely by the donors. This has undermined government efforts to deliver effective maternal health services.

This illegal sale of blood is happening mostly in private hospitals but also in government health centres especially those in the villages where mothers do not know that blood is supposed to be free.

Michael Mukundane, the Spokesperson of Uganda Blood Transfusion Services says it has been very difficult to arrest or bring evidence against the medical officers who sell blood to patients.

“We know it’s unethical but it’s been very difficult to bring evidence because the caretakers of the patients don’t give receipts which would be used as evidence against those involved,” he said.

The Uganda Blood Transfusion Services has now resorted to a campaign intended to educate patients and their caretakers that blood is not for sale so that they don’t pay if a health worker asks for payment.

“We have been using posters pinned in hospitals, car stickers and many other channels to tell people that blood is supposed to be free,” he said.

He also says that the caretakers of the patients do not report the culprits for fear that their patients could be harmed by the health workers.

Anne Lumbasi, a Senior Program Officer at Centre for Health, Human Rights and Development, a Non-Governmental Organisation that fights for maternal health, sexual reproductive health says they get many complaints about illegal sale of blood.

The same organization has been helping Omony through a court case to get justice for the death of his wife. Lumbasi says they recently won a case on maternal health that requires the government to finance and support women and girls giving birth to ensure that they have all they need to fulfill their maternal health function.

“In Uganda, we have seen mothers who are dying because they cannot afford blood, or they went to hospital and did not find blood,” she says.

Statistics show that annually, Uganda needs over 340,000 units of safe blood, but usually Uganda Blood Transfusion Services collects about 200,000 or even less.

The situation was worse during the COVID-19 lockdown, because most of the donors are school going children who were locked away from school.

This illegal sale of blood also discourages people who donate this priceless item that cannot be manufactured.

“Imagine someone who has been donating blood goes to hospital with their patient or loved one in hospital and they can’t get blood because they have to pay! That really puts down the efforts that the Uganda Blood Transfusion Services is doing,” Lumbasi says.

The Ministry of Health Permanent Secretary Dr Diana Atwiine has come out strongly to condemn the vice which has continued in both private and public health facilities.

In 2019, the former minister of Primary Health Care Dr Joyce Moriku Kadicu warned that the government would do an audit of how blood is handled in health facilities especially private facilities across the country but it hasn’t been done.

“I think it’s just laxity on the part of the government to leave the private sector to do whatever they please. It shouldn’t be about the money, it should be about people’s lives,” Lumbasi says

The 2020/2021 Ministry of Health report on maternal health put hemorrhage as the leading cause of maternal death at 48.5%. A year earlier, the Uganda Health Demographic Survey showed the country loses 16 mothers every day to postpartum.

Isaac Ojore, who has been a regular blood donator says it’s disheartening to donate blood to help patients and mothers but the health workers sell it.

He says Ugandans especially the caretakers of patients in these health facilities should develop confidence and report these unscrupulous health workers.

“I know there is that fear of what the health worker might do to their loved ones but there is a need to build confidence within the population to be able to bring to book these health workers. So that they are accountable and end this vice,” he says

He says it’s disheartening that the mothers go to hospitals to bring into the world new lives but they end up losing their lives.

If this vice continues, Ojore warns that the number of blood donors might start reducing because they will lose the morale to donate blood.

And if the population is discouraged, the number of blood units collected annually might dwindle and this puts not only maternal health but the whole national health care system in jeopardy.

This investigation was done with the support from African Journalism Conference, the Gates Foundation and the Henry Nxumalo Foundation