By: Robert Madoi

The coronavirus pandemic has left the world reeling from a body blow like no other. The irony of this is that the pandemic was initially seen as the quintessential equaliser. As the novel coronavirus crashed through the trapdoor into an unprepared world, global citizens were told Covid-19 would end up — however improbably — not making fine discriminations between rich and poor. The deadly virus has however turned out not to be a grand leveler as much as an amplifier of existing inequalities, injustices and insecurities.

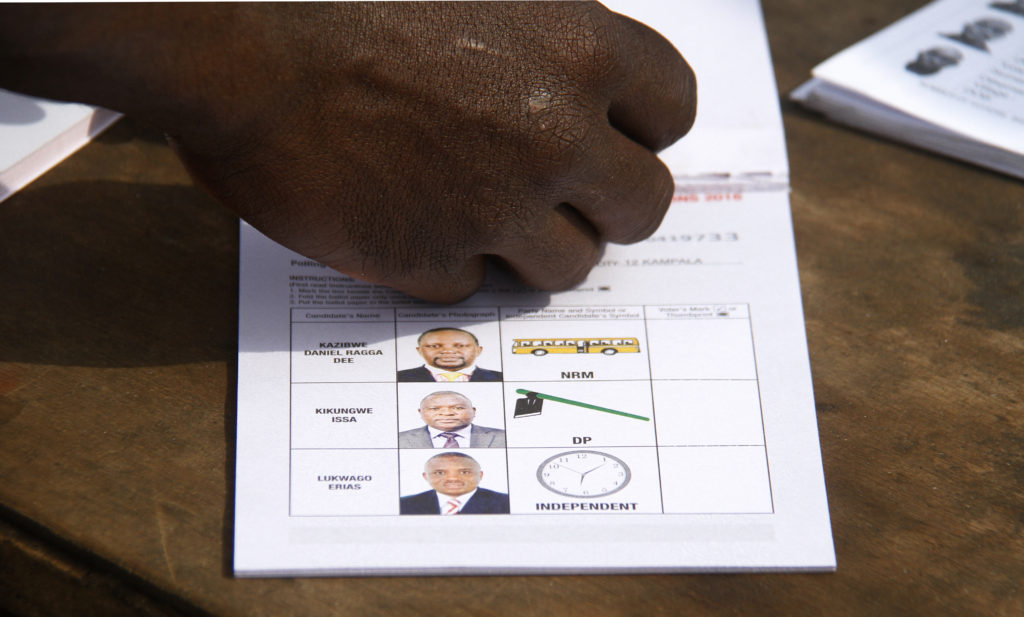

For African countries like Uganda, which go to the polls in a few months, there is no guarantee of a benign outcome to this extraordinary event. With the pandemic straining resources of the vulnerable poor, voters could yet set great store by the ability of candidates to be lavish with money and other such inducements. This is hardly a novel problem for Ugandans. During electioneering, voter bribery tends to flood the collective unconscious of people.

Monetisation of politics

A fine-grained study by Alliance for Campaign Finance Monitoring conducted in 2019 established that nearly Shs 2.5 trillion was splashed out by parties and candidates during the 2016 electoral cycle. The exploration also shone a light on the 2021 electoral cycle, with a guesstimate putting the cost of funding a shot at a seat in parliament anywhere between an eye watering Shs. 500 million and Shs. 1 billion.

The weight of evidence in presidential races further illustrates the culture of gung-ho expenditure. The European Union Election Observation Mission’s final report on the 2016 poll revealed that candidate John Patrick Amama Mbabazi funded the Shs. 3 billion campaign out of his own pocket. The report also noted that Kizza Besigye’s “expenses totaled Shs. 1 billion, of which Shs. 96 million were donations.” Yoweri Museveni’s campaign team was not forthcoming with the valuation let alone source of his campaign funds.

The report also offered an alarming glimpse of the extent to which voter bribery is rampant. It noted that, “voters expect to receive money, food, refreshment, or other goods.” Indeed, voters are hardly passive recipients of inducements that leave them with little choice than to command blind obedience. In 2011, the mission’s report stated in no uncertain terms that “the distribution of money and gifts by candidates especially from the ruling [NRM] party” is “a practice inconsistent with democratic principles.”

The Alliance for Campaign Finance Monitoring’s 2019 study made no attempt to hide the fact that voters gladly play the role of instigator in chief. The civil society organisation’s most recent study whose findings were made public at the backend of August conflates commercialisation of politics and capture of state institutions. “The cost of campaigning [is] so high. Individuals that do not have access to campaign money have been technically knocked out of the competition,” says Alliance for Campaign Finance Monitoring Executive Director, Henry Muguzi.

Show me the money

But with the pandemic having left many Ugandans at the edge of an existential threat, it will be a task of considerable complexity to sell the niceties of issue-based campaigns. Money will talk, and talk big. Here is why voters will be shrieking, ‘show me the money!’ The government expects the budget deficit to widen to about 2.5% of GDP because of the pandemic. The economy is consequently expected to shrink by 3.5% this year, wiping off the market at least Shs. 3.9 trillion. While the economy showed green shoots of recovery in July, most Ugandans have continued to face a threat of unprecedented magnitude.

The Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development recently revealed that the Great Lockdown adversely affected 2,727 employees. The grim statistics indicate that 998 employees had their contracts terminated. A further 951 were sent on unpaid leave, with 129 suspended. Twenty-six employees were re-designated as part-time staff while 623 had their salaries and wages cut. UNDP Uganda warns in one of its Covid-19 policy briefs that “survival could imply adoption of negative coping strategies.”

In the midst of an electoral cycle, survival could translate into being complicit in voter bribery. The common thread in the lead up to the 2021 poll looks set to be a desperate attempt by voters to keep their heads above water. In their desperation, voters may punch lower and harder as they look to butter their bread. Richard Todwong is one of a handful of NRM stalwarts that do not exude an old fashioned toughness while defending perceived ills. Renowned for his economy of effort, the NRM deputy secretary general was quick to simplify a complex problem after an event-filled delegates conference. He told the media thus: “However much you spend money; if people don’t like you, they won’t vote for you.”

The new [ab]normal

Campaigning during the delegates conference was essentially not different from the likes of which had been seen pre-pandemic. Candidates enjoyed rope lines and handshakes. It remains to be seen whether campaigns in the lead up to the 2021 general elections will involve literally being elbow-to-elbow. The Electoral Commission has been consistent in stating that a “hybrid approach” will shed most — if not all — tried and tested campaigning methods. For voters who were dazzled by the theatre of it all, the new normal could well be an abnormality.

The Alliance for Campaign Financing and Monitoring estimates that presidential candidates spent nearly Shs. 860 billion in the lead up to 2016. Successful parliamentary candidates meanwhile fell short of the Shs. 25 billion mark. With candidates likely to conduct small-scale meetings with voters from door to door, the distribution of largesse will doubtless be ossified. This is a microcosm of a vice on a broader scale.

Elections in Africa are the most expensive in the world per capita. The sheer number of people needed to organise an election in Africa make the experience such a logistical nightmare. Africa has held approximately 220 presidential elections, 370 parliamentary elections and 130 referenda between 1957 and 2018. The conservative average cost for conducting an election on the continent is pegged at an eye-watering $200m per election.

The average cost of conducting elections globally is US$ 5 per voter. The 2021 poll in Uganda is expected to top that average by US$ 7 (increasing to US$ 12). If it does, it will maintain an unwanted record of rising steadily and relentlessly. In 2011, the per capita cost was US$ 7.1 before marginally increasing to US$ 8.7 five years later. That translated into an expenditure of Shs. 419.9 billion. In February, the Electoral Commission indicated that it would need Shs. 868.14 billion to organise the 2021 poll. The 106% jump in spending left many perplexed, but not entirely so.

The dark arts during an electoral cycle are such that making the proverbial kill is an achievable aspiration. While Covid-19 might have actors one end of the spectrum boxed in (Finance minister, Matia Kasaija in May wrote to the World Bank requesting a $300 million credit line to avert a macroeconomic crisis), voters at the other end could anticipate a get-out-of-jail-free card. The path in times of coronavirus never did run smooth.

Robert Madoi is a senior journalist, editor and academic based in Kampala