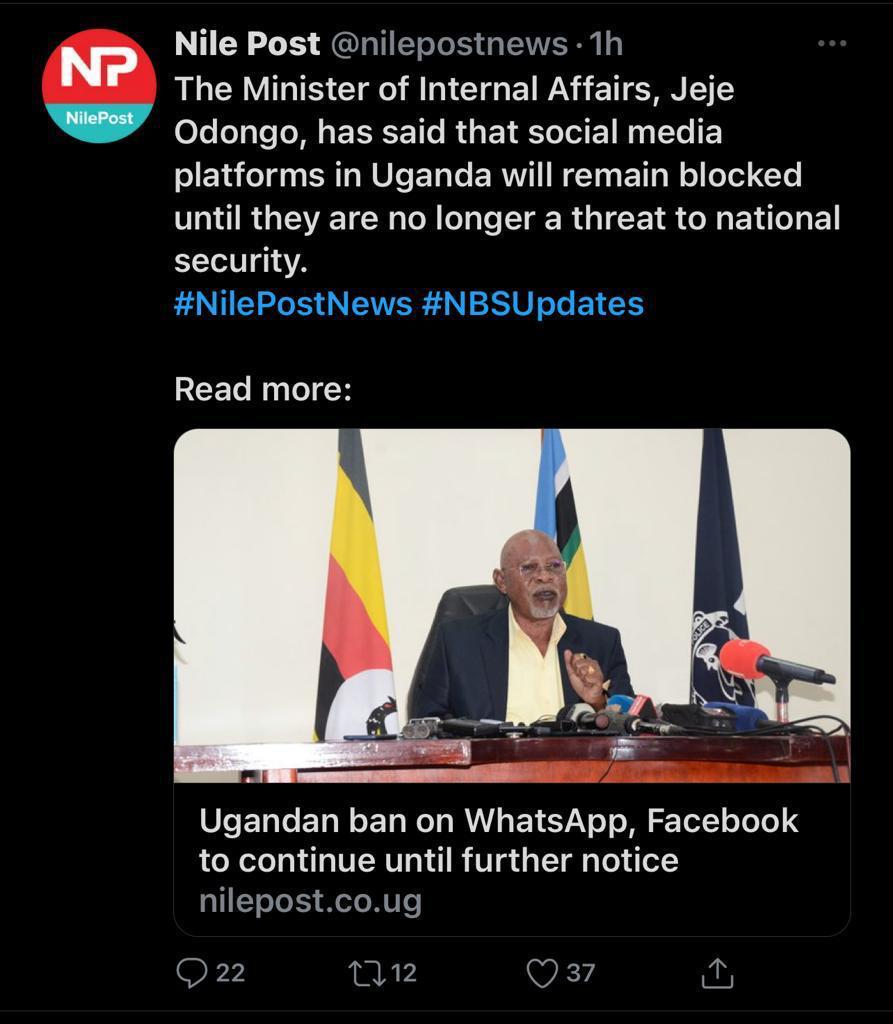

The beautiful Republic of Uganda, christened in 1908 ‘the Pearl of Africa’ by British explorer Winston Churchill, has emerged from what started off as a not-exactly hotly contested election but ended up as one. A lot has been, will be and probably should be said and written about this, the East African country’s sixth election since the 1995 Constitution was promulgated. A prominent feature of this contest was the Great Internet Shutdown. It was expected. We had walked that road before. In 2016, the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC) ordered telecom companies and internet service providers to cut access to social media. Virtual Private Networks (VPN) came in handy. Then the state polished its tool box of tricks and blocked that too. Days on end, a communication blackout engulfed the nation fathered by Milton Obote in 1962. Radio, word-of-mouth, television and the newspaper regained lost ground in this largely agrarian society.

The 2016 action was challenged in court by busy-body activists accustomed to ambulance chasing and the suit dismissed. Under the Uganda Communications Act, 2013, UCC and the telecom companies would be acting within the law, if you ask me, albeit the morally reprehensible nature of their actions and the political ramifications to especially the legitimacy of a poll where access to mobile money, internet, free flow of information is curtailed. It felt like a script written by a gang that turns off the electricity supply in an area so that they can loot the village in the comfort of darkness. But then there are national security considerations, the state contends. This is an argument that even one of the world’s most prized judges, Lord Alfred Denning, tended to lean towards to; once arguing that when it comes to national security, that which we cherish called human rights, take second place. The line between regime security and national security though is thin. National security for instance, has been used as an excuse for gross human rights violations by advanced liberal democracies like the USA and the United Kingdom in their war-on-terror post 9/11, often time pitting Muslims against state security agents, downloading all shades of prejudice against suspects whose first crime is being Muslim.

In countries like Kenya, national security, as an Aljazeera film a few years ago demonstrated, has been a blank cheque for the state to assassinate Muslims without regard to due process. Their crime? The suspicion that they are wrong elements posing a threat to national security. This line has been used to suppress, maim and kill Muslims by America, UK and its compradors in Africa such as those in East Africa and West Africa. If one has an axe to grind with a Muslim, the short cut to settling the score is to, using one’s connections in the system, accuse them of being a suspect in a fictitious terrorism plot. No need to arrest, investigate and let the fellow have their day in court. Shoot. Dead. National security. No questions. The film by Aljazeera, “Inside Kenya’s Death Squads’ paints a graphic illustration of how this is happening in our world as does a wide range of literature on USA/UK/Israeli operations across their spheres of influence in their creepy war-on-terror which has progressively mutated into a war-against-Islam by predominantly Christian nations drunk with power and naked imperialism, ready to destroy anyone that stands up to their destructive capitalism (as Naomi Klein calls it) and neo-colonialism enterprise. It starts with, under the national security cover, demonizing and criminalizing an entire religion. Yes, the invasion of Iraq by USA and UK was another national/global security button pressed wrongly and based on weapons of mass destruction invented in the heads of George Bush, Tony Blair and their security infrastructure. The national security argument then prevailed over logic and reason. Bush and Blair’s troops committed genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and reduced a thriving nation to misery. Hail national security. They then conscripted allies across the world using the infamous mantra, “you are either with us or with them.” Their cronies, like the masters, have since used national security to curtail opposition politicians, contain critics and kill radical Muslims in the name of fighting terrorism.

The point, therefore, is that the national security argument, whereas valid sometimes, is not water-proof. It’s neither here nor there. The pendulum bob of convenient interpretation and application can swing anywhere. Ultimately, the law, as a re-enforcement of power/class relations will favour the ruling class who shape the narrative arising from their control of the mediums through which discourse is brewed.

That said, we are happy to, for argument’s sake, give the men and women charged with the protection of our lives and property, and ensuring that our society remains a cohesive entity; an eco-system of unity in diversity, the benefit of doubt. Let’s also give, again, for argument’s sake, the critics of the Great internet shutdown, the benefit of doubt. There is an idea out there, they proclaim, that to be able to meddle with the election process, the state just shut down the internet space. Or, as President Museveni argued, if Facebook blocks accounts of the ruling party’s stalwarts for what were not exactly convincing reasons advanced by the Silicon Valley tech-giant, the state can, using King Solomon’s wisdom, retaliate and freeze the whole thing altogether. Whichever way one looks at it and depending on their political inclination, the shutdown of internet merits discussion beyond our sentiments and mutual suspicions.

It merits discussion even more because two developments stood out, preceding the Great Shutdown. UCC wrote to Google and You-Tube asking them to look into and consider suspending accounts of National Unity Platform (NUP) party loyalists deemed foul-tasting to and by the powers that be. That request fell on deaf ears. Then Facebook blocked accounts of National Resistance Movement (NRM) cadres. Facebook’s explanation was, to say the least, silly and does not deserve repetition here.

Both government of Uganda and Facebook’s moves were pointless. Futile for government of Uganda to opt for a shutdown of accounts critical of it and for Facebook to block accounts of NRM cadres. Rather than foster public debate, however ferocious the arguments get, both Facebook and government of Uganda went for the switch. Both actions are, in my considered view, an analog solution to digital problems. They reek of ‘those bad days’ when governments would close newspapers as happened to Jesse Mashete’s Weekend Digest when Dr. Kizza Besigye was state minister for internal affairs. Mashete told me in an interview not so long ago that Kawanga Ssemogerere, then internal affairs minister, had declined to order the shutdown of the newspaper without a court order after it published sensitive material on the murder of Andrew Kayiira. Besigye, the vibrant NRM cadre then, did the job as Kawanga coiled his tail. Mashete eventually fled to exile, sued the president and returned home. In the legacy media realm, governments were spoilt for choice.

They could as well order that journalist X be fired by the employer or freeze advertising as happened to the Monitor newspaper in the 1990s or keep the journalist and editor in court corridors as happened to Andrew Mwenda and Charles Onyango Obbo. Worst case scenario, in classic Idi Aminsque style, just make it risky for the press to write or say anything that irritates the emperor as Ben Bella Ilakut can attest with the famous ‘Amin rapes Nyerere’ story. In Milton Obote’s Uganda, the distance between jail and the newsroom could be shortened once the powers that be determined one’s news product or commentary toxic. One can go on and on, surveying the entire African continent and beyond over the last 100 years as Konrad Adenauer Stiftung Media Africa program has done with their compilation of investigative journalism exploits in southern Africa for the last century. Reading that collection, you appreciate just how much power both pre and post-colonial governments wielded over the press.

That power has always been multi-dimensional and can be traced as far back as 1440 with the emergence of the Johannes Guttenberg press and how it enabled mass printing and production of books and literate items. It expanded access but also reconfigured it by shaping (altering?) the political economy of production processes (licensing, access to resources for printing costs, language/education levels, regulation, competition, et al). Limitation of access has always manifested itself in one way or the other. If one wasn’t limited by the state, the market did (we can revisit the debate on monopolies and corporatization/commoditization of news) as well as advertising dynamics in determining what we consume. There was, in substance, nothing mass about this but everything exclusionary, nay elitist about it until radio and to some extent television emerged but they too got stuck in the labyrinth of the political economy of the production of meaning as Stuwart Hall calls it; the output is/was a product of processes that are controlled by those who wield power. Again, there was, in substance, nothing mass about radio and Television. The digital media space is the closest to anything mass there has been in the last two centuries. I say closest mindful of its own limitations.

Redefining the Public Sphere

Our public sphere, interpreted through the lens of German philosopher Jurgen Habermas as, “made up of private people gathered together as a public and articulating the needs of society with the state,” has always been a tightly monitored and guarded space with inhibitions either by the market or some socio-political force or authority (including religion as the Charlie Hebdo-Prophet Muhammad cartoon saga shows). Even then, the Habermasan public sphere had/has inherent limitations in and of itself as enumerated by American philosopher and critical theorist Nancy Fraser in her work, ‘Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy.’ Fraser, offering a feminist revision of Habermas’ definition of the public sphere, lifts the veil on the exclusionary nature of the so-called public sphere. This exclusionary nature is synonymous with the waning legacy media enterprise. Government of Uganda, like Facebook, acted in a manner that fits in the frame of the old-school exclusionary tendencies of hegemonic media and states/markets. They are chasing wind because they lost that power (to exclude) and any attempts at regaining it can only be counter-productive and short-lived. The joke is on the state.

Therefore, the digital revolution, to use Museveni’s words of 1986, “is not a mere change of guards but a fundamental change,” nay a structural re-configuration of how we connect, communicate and make sense of our world. Where the state had so much power, that power has considerably waned. Where the market used advertising, commoditization and market-entry barriers to limit who could play in the information field, the digital space has lifted that barrier and expanded access with internet penetration in Africa averaging 39.3% (meaning four in every 10 individuals uses the web as of 2020). Effectively, even Facebook and Twitter exercise the current power to exclude sparingly and have to offer explanations.

Where editors and media executives had the final say on what the public could consume through their gate-keeping function, the digital media space makes everyone their own editor, producer and broadcaster/publisher. Mark Zuckerberg and his friends at Twitter probably didn’t envision just how tumultuous their innovative genius would turn out. In Europe now, the debate is hinged on aspects of taxation, revenue sharing with legacy media houses (in Australia recently) and across the Atlantic, clouds of confusion abound on the question, ‘how do you deal with these tech-giants?’ They have become too big and governments aren’t sure which part of the mahogany tree to cut or even which tools to use.

Enter counter publics

What does this mean? Fraser spoke of subaltern counter publics as, “discursive arenas that develop in parallel to the official public spheres and where subordinated social groups invent and circulate counter discourses to formulate oppositional interpretations of their identities, interests and needs.” What is Fraser saying here? In essence, the down-town lass and lad who could not find voice in the legacy media space (an exclusionary public sphere controlled by those who wield economic and political power) has now found voice on social media, a parallel arena which the state has limited control of and the market’s inhibitions are also limited. No surprise therefore, that it is possible today to build a movement such as #Black Lives Matter, #Fees Must Fall and Arab Spring using this ‘alternative media’ whose subaltern counter publics have thrown off the shackles of limitations synonymous with the state and market, whose control of the discourse (call it manufactured consent like Noam Chomsky would) since the Guttenberg era-conditioning of society has been challenged. It is, in more ways than one, the end of an era (error?) where political and economic power conditioned society through the media. Of course, there still exist limitations even with this new medium (such as internet access, costs, digital literacy and manipulation through disinformation and misinformation).

Fraser’s viewpoint has upgraded from a critical theory outlook to an everyday reality of our socio-political ordering of life. The 18-year-old lad at a slum in Kamwokya has as much say about the politics of the day as does Prime Minister Dr. Ruhakana Rugunda on Twitter. They can talk to the president directly on his social media platforms. In the olden days, Rugunda enjoyed limitless access to media and the president had control over which comments got aired when he is hosted on a radio show. Today the ghetto bloke, at fairly affordable cost of internet, has his way. Some even hurl obscenities at their leaders and feel cool about it. A shutdown worked in the old age but is unsustainable in a world interconnected by the internet. You could close a radio station and half of the country would not know or care but closing the internet space means closing ordinary course of business at the central bank, freezing the banking sector whose activities are largely internet-driven now, and a halt of government’s own transactions that are hinged on the internet. In the era of tele-medicine, this means bringing to a halt critical medical processes. You basically hurt yourself. Government, aside from revenue loss, suffers more when it shuts down the internet for its operations are now largely driven by the web and with internet considered a human right now, you can only secure pyrrhic victory from such actions, in so doing, affecting your national image which in the end increases marketing costs for the tourism sector where perception is mightier than reality.

Way forward

What then, does one do? You don’t adopt analog solutions for problems of the digital age as Facebook and government did. You build your own capacity to engage, robustly debate and allow the cross-pollination of ideas (including the most abhorrent ones). Sometimes the internet space gets contaminated with disinformation and misinformation. That is not entirely new, anyway. Even the Bible talks of false prophets so fake news has been a part of the human race since time immemorial. Oh yes, even Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de’ Galilei (1564-1642) was seen as a prophet of fake news by the Church. Traditional media too had/have their own share of fake news, including Pulitzer award-winning stories later discovered to be fake. You don’t deal with fake news by closing the internet just like you don’t close a newspaper because of one bad story. You exercise discretion and discernment to isolate the maggots from the mushroom (Iteso call it aise ikuru obale) and prepare diner. What UCC and security agencies did is throw the whole mushroom.

You do not ask Google or Facebook to pull the plug, you constitute capacity to counter your critics, the reason fact-checking organisations are now mushrooming across Africa. You respond in real time and up your communications game to match the challenges of the day. States like USA that accuse Russia of interfering in the election(s) using the internet would, using the Ugandan approach, have had the skies fall on earth had they considered shutting that space. They engage and precisely go for the tumors in the body, including calling Vladmir Putin out.

They have eyes but they don’t see

And then what do you do with a political group preaching and/or glorifying hate, sectarianism and violence as NRM, People Power/NUP and Forum for Democratic Change supporters do occasionally? Again, this is not unique to social media. This has happened since time ancient. The criminal law books of Uganda, like several other countries, are draped with sanctions for offences that take care of abuse of social media in whatever form. The Computer Misuse Act, the Anti-Terrorism Act, the Penal Code Act, the Anti-Pornography Act and several others, give the state the legitimate legroom it needs to deal with miscreants who overstretch the freedom of expression and speech beyond acceptable limits. In fact, the British statesman, John Stewart Mill (1806-1873) in ‘On Liberty’ came up with the ‘harm principle’ and argued that individuals’ actions should only be limited to prevent harm to others. He was, of course, building on established arguments advanced during the French Revolution in, ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen’ of 1789. Accordingly, across the globe, including in liberal democracies, press, expression and speech freedoms exist within four walls and a ceiling of limitations that speak to the Stewart and French revolutionaries’ arguments advanced in the 19th century.

Therefore, across history and geography, human societies have recognized that the freedoms that we enjoy are not absolute and ceded power to some, amongst us, acting in the public interest, to evoke sanctions necessary to maintain the contours of cohesion that distinguish the human race from say, the jungle law of the animal world. If one does not find sufficient comfort in the criminal code, defamation law has evolved over the last 100 years to take care of grievances one may have against another over published material deemed defamatory. Lee Kwan Yew, ex-Prime Minister of Singapore, was effective when it came to taking on defamatory publishers in Europe, America and his own country. Civil law remedies, therefore, are available both for the mighty and hoi polloi, including for other violations such as intellectual property law and the right to privacy.

It follows therefore, that what Facebook did in blocking accounts of NRM cadres (as Twitter did with Donald Trump) instead of letting them face off with People Power supporters online, was not only abuse of their rather too powerful abilities to determine the limits of free speech (this is being contested in America and Europe) but also shadow boxing out of touch with the very strengths of their own revolution. You can close Duncan Abigaba’s Facebook account and in a minute he has 100 others using different names, manned from an office at Majid Musisi Close in Muyenga. In equal measure, UCC’s decision makers and the security infrastructure behind such choices as closing the internet space, are successfully failing at imagination and indulging in a rather counter-productive attempt at rewinding the clock instead of catching up with the times. They are groping in the dark. It is, one can add, another manifestation of laziness by NRM’s propaganda machinery; so rather than engage and take critics head on, they turn to the switch, hurting themselves more in the process, drawing more antipathy for the regime. At the very least, it is a reminder that tolerance levels in our fledgling democracy are dwindling and more importantly, that as a peasant society, ours is analog solutions to digital problems.

Ivan Okuda is an Advocate and Managing Editor, www.voxpopuli.ug.