A look at the twenty years of political activism of the four time presidential candidate

By Ian Katusiime

When Dr. Kizza Besigye went to address his party faithful on Aug. 19 at the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) headquarters in Najjanakumbi, Kampala, he found himself in familiar territory thanks to the towering influence he has had over the party since its founding.

The sense of anticipation among supporters was palpable amidst a ranging pandemic. There was little adherence to social distancing and other health guidelines at the event just like across the country as the political season was building up. For other supporters, especially senior party figures, the decision by the party honcho was no longer a secret.

Besigye was accosted by jubilant FDC youths who first prevented him from addressing them until he picks presidential nominations forms. For the young men stomping the ground in wild ululations of their hero, it was, however, a disappointing moment as the four time presidential candidate confirmed the news of what had been floating around for weeks – that he would not contest in the 2021 presidential election.

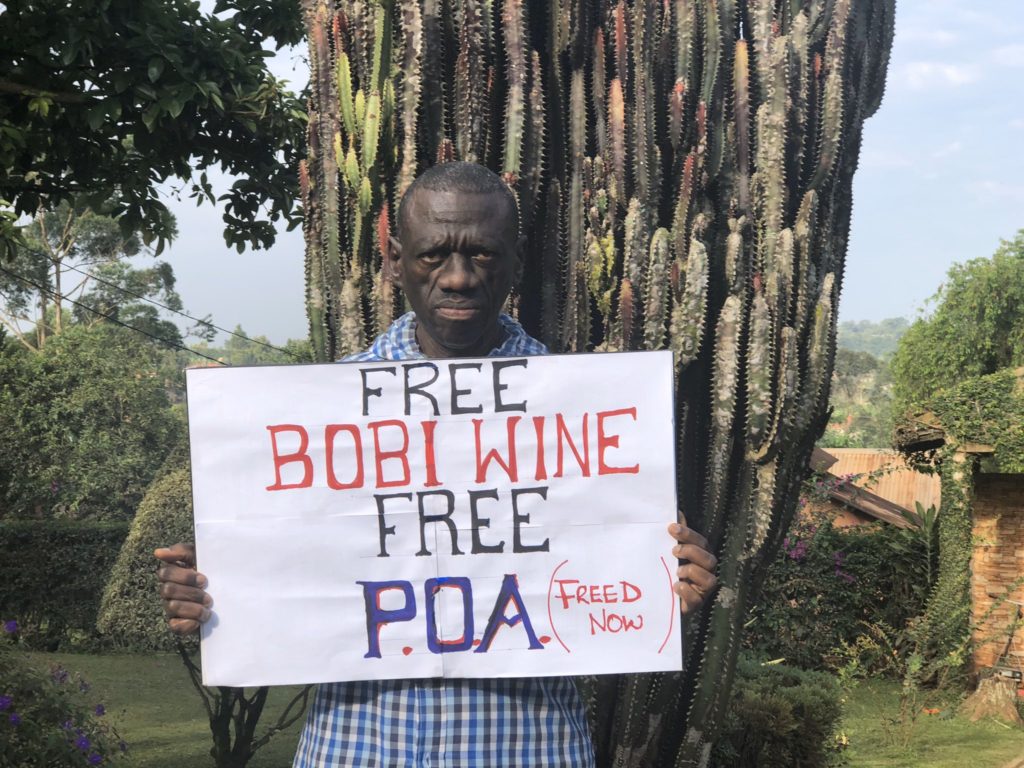

“Never ever imagine that I can leave the struggle,” Besigye declared to a cheering crowd of loyal supporters. Dressed in his usual checked blue jumper that has become the symbol of his activism against what he terms a military dictatorship, it was vintage Besigye. He reiterated the struggle that lies ahead to members of the largest opposition political party in Uganda.

With the benefit of hindsight, some observers argued that Besigye had made the right decision not to contest for a fifth time against his former comrade, President Yoweri Museveni, in what he and sections of the electorate have consistently called an unlevel playing field.

A victim of constant arrests, blockades on his home, a plethora of trumped up charges, Besigye has borne the brunt of being an opposition leader in a fledgling African democracy. One of the first and youngest ministers of the National Resistance Army/Movement (NRA/M) government, and also one of its leading ideologues, he has run the gamut of what it means to fall out with a revolutionary government one helps bring to power.

From 2001 when he first stood up to 2016 at his fourth attempt, Besigye defined the presidential race. With each election, he played a different card as different circumstances surrounded almost every election. Actors both in the ruling party and the different shades of opposition have in the past few weeks been musing over his impact on Ugandan politics.

Proscovia Salaamu Musumba, former MP and now vice president of FDC, says for the 2001 race, Besigye was in the “political laboratory.”

“He was testing the system they had built along the way and he realized it had been hijacked.” She adds, “He was in a political laboratory and it confirmed that nothing had been learnt after the 1981 war.”

Musumba recalls the election as a very violent one. “It took the whole country by storm and the violence meted out was disproportionate. It set the tone for the high contestation we see in politics today.”

She says that for the state and the NRM system back then, Besigye’s run was an indescribable journey “from shock to acceptance”.

After the chaos of the 2001 election, which was strongly reminiscent of the one held in 1980, Besigye dashed into exile, ending up in South Africa. It was while there that he and likeminded individuals in Uganda made the monumental decision to form FDC. It was a union of Reform Agenda and Parliamentary Advocacy Forum (PAFO).

Birth of FDC

There were a lot of disagreements about ideology, politics and the position Besigye would occupy in the party. Some of his close associates flew to South Africa and had animated meetings with the future party leader. After a lot of back and forth, with equally tempestuous meetings held in Uganda, FDC was formed in December 2004 with the dramatic presidential nomination of Besigye a year later.

Important to note that the new party was dominated by a breakaway faction of NRM who were from the western part of the country just like Besigye. Members of this group had, earlier on before Besigye’s run in 2001, urged Besigye to let Museveni serve out his constitutionally guaranteed term to 2006.

This was in the hope that Museveni would not amend the constitution to remove term limits and run for an unprecedented third term in 2006. Besigye was convinced Museveni was not ready to give up power and he felt vindicated when the movement to abolish term limits kicked off.

When this move gained momentum in 2003, it equally laid the ground for FDC as an alternative political home for Westerners and other Ugandans who saw the NRM increasingly as a one man show.

However, Besigye did not just suddenly break ranks with the NRM in 1999. He was already in anguish at the turn events that were taking place in government years earlier. He had observed how Museveni would bristle at even the slightest questioning of his authority. Besigye was confiding in colleagues like Gen. David Sejusa and others in the army about his disquiet.

He was at loggerheads with insiders like Gen. Salim Saleh, the President’s brother, on the unchecked corruption and what he deemed unilateral decision making in government. It can therefore be argued that the Museveni-Besigye fight is a 30 year duel.

Looking back, Musumba muses about the inevitability of FDC and the groundwork Besigye laid.

She says that thanks to Besigye’s efforts, FDC has done well and is still a force to be reckoned with. “It is still a robust party offering leadership.” Musumba says FDC answered the clarion call at the time it was formed and stresses that “It is still relevant to the political needs of the population.”

In the epoch-making 2001 election, Besigye worked with a number of actors, some of whom have become mainstays on the political circuit. These include Reagan Okumu (Aswa County MP); Patrick Oboi Amuriat (FDC president), Joyce Ssebugwawo (Rubaga Mayor and FDC vice president for Buganda region); Winnie Byanyima (who contested for MP for Mbarara Municipality and won, currently UNAIDS executive director).

Others are businessman John Garuga Musinguzi, Winnie Babihuga, then Rukungiri Woman MP. Some members of Besigye’s 2001 team have passed on: Sam Njuba, Sulaiman Kiggundu (former FDC national chairman), Bwanika Bbaale, the latter at the time of his passing last year was FDC district chairman Luweero.

The events of the 2001 election – the arrests, harassment and the cathartic experience of Besigye’s decision to stand against Museveni – were documented in a semi-autobiography titled Kizza Besigye and Uganda’s Unfinished Revolution by journalist Daniel Kalinaki.

When the FDC was formed in 2004, and became a fully-fledged political vehicle to take on the juggernaut that the NRM had become, Besigye and his allies had started a fire that the state could not fathom.

Before Besigye decided to run, the press had been perceived as the main foe of the NRM and internal dissent was quietly and effectively suppressed.

Journalist Charles Onyango Obbo alluded to this in a recent interview with NTV discussing the impact of Besigye breaking ranks with NRM in 1999. “We were being called multi-partyists which was an insult. Besigye took that monkey off our back.”

Disgruntled with government and what he deemed creeping authoritarianism, Besigye had just published his famous document: ‘An Insider’s view of how NRM lost the Broad base.’

It was a taste of things to come in the years ahead.

Walk-to-Work

The Besigye-led Walk to Work protests that started in 2011 were a different kettle of fish from the presidential election petitions that were lodged after his first two contests in 2001 and 2006. The walk-to-work protests were arguably the most organized form of resistance the NRM government had faced in its then 25-year existence.

A brutalised Besigye with arm-in-sling is still engraved in the minds of Ugandans as a price for political opposition. The single handed actions of Gilbert Bwana, a state agent, cracking the window of Besigye’s Prado and showering him with pepper-spray, cast the opposition stalwart as a sympathetic figure in the Ugandan psyche.

The height of the brutality meted out against walk-to-work protesters was the killing of two year old Julian Nalwanga in Masaka district. She was shot inside her homestead as security forces quelled a protest in the area. Various reports say nine people were killed during these famous protests that spread across the country.

Walk-to-Work festered for about two years and, at the time, Kampala had become a cauldron of anger, frustration and anxiety as police battled opposition and any whiff of protest in the central business district. To that effect, the government passed a controversial law, the Public Order Management Act (POMA) to contain any semblance of opposition.

The protests gave birth to pitched battles between aggrieved citizens and their government. From piglet-carrying self-acclaimed ‘poor youth’ expressing outrage at the profligacy of parliament to opposition MPs demanding for release of their own, Kampala turned into a nerve centre of political agitation.

An aide of Besigye and now Buhweju County MP, Francis Mwijukye, spoke to this journalist in an earlier interview about Togikwatako, the campaign against the amendment of the presidential age limit in 2017 and the significance of the protest movement in Uganda.

“Togikwatako has been embraced by people from all walks of life; academia, farmers, the rich, poor, musicians, they are all speaking with the same voice,” he said, “When you see all these people speaking up it is because of the spirit of Walk-to-Work.”

Mwijukye further explained “To merely list the successes of Togikwatako is not to appreciate the earlier setting up of structures of defiance. When you see people wearing red ribbons everywhere, it is because they have been empowered by defiance.”

Mwijukye was a fiercely loyal aide to Besigye before he was famously elected to Parliament in 2016. He volunteered as a bodyguard to the veteran politician and at the height of the walk-to-work protests, his image fearlessly warding off police constables from Besigye’s white Pajero was hard to miss.

Those who have followed politics in Uganda have drawn a lot of lessons and conclusions from Besigye’s election runs. One of the lessons has been the doctor’s impressive vote tally, something that is unlikely to be replicated anytime soon by an opposition politician.

Besigye bagged over two million votes in the first three elections against Museveni, and notched one million more votes in the 2016 election. It will be a test for the new kid on the block, Bobi Wine, who has galvanized a disgruntled and bulging Ugandan youth population, to do the same or even beat the record.

When Besigye and Muntu faced off in a televised debate for the FDC presidential flag-bearer in 2015, Besigye told Muntu that he was guaranteed of two million votes when he stands for President at the national level, given that he had scooped the said number of votes in the three elections he had, by then, contested in.

Besigye was directly challenging Muntu, then party president, on his potential for attracting votes. True to form, Besigye electrified the presidential campaign from nomination day with adoring crowds gifting him sofa seats, money, chicken and other goodies.

Some of the adoration has been born out of the adversity Besigye has endured during his struggle. He had suffered so many beatings and teargas attacks at the hands of police. In 2007, his brother, Joseph Musasizi Kifefe, succumbed to injuries from long detention and torture related to his political activities.

Andrew Karamagi, a lawyer, says he came to admire three traits from Besigye after working closely with him during the 2016 election.

“His attention to detail was apparent in the process of jointly drafting documents pertaining to The Democratic Alliance (TDA),” Karamagi tells Leo Africa Review, “His capacity to put in really long hours of deep thought, passion and concentration over the issues at hand.”

TDA was a loose coalition of opposition figures involving ex-Prime Minister Amama Mbabazi in the build up to the 2016 polls.

He states that the third trait was, and still is, Besigye’s unwavering commitment to a better country. “It shines through his words and actions. I am more than glad to have learnt a lot from him.”

After the opposition maverick bowed out of the 2021 election, Karamagi had this to say over the former opposition leader’s contribution to the development of Uganda’s polity.

“If you think about how venerated the person of Yoweri Museveni was in the nineties, you would understand why I equate Dr. Besigye to those who challenged the infallibility of King John and, through concessions like the Magna Carta of 1215, were able to secure certain rights and freedoms.”

Karamagi says due to Museveni’s intoxication with power, someone had to swim against the tide and challenge the “harmful deification of the Ssabalwanyi (chief fighter)”.

“Dr. Besigye brought Museveni back to earth.” He adds, “This is an immense contribution to our polity’s democratisation journey.”

Karamagi who has led demonstrations against the government says it was due to the efforts of Besigye that people like him who were toddlers in the nineties during Museveni’s untouchable years, can now stand up to challenge Museveni’s policies, politics and practices.

“Besigye did not allow him to become a god of sorts even though Museveni today very much resembles African tyrants of the eighties and nineties.”

In turn, one of the criticisms Besigye faced was that he was unwilling to back down from the fight he had started by staying on the ballot. He and his supporters always retorted that the attention should not be shifted from a president who has ruled for thirty five years. Therefore his decision was treated by his camp as a tactical disarming of critics.

Silent warrior

Brian Atuheire, a parliamentary candidate for Kinkiizi West, who regards Besigye as a mentor, describes the former presidential candidate as “a very free guy and kind hearted man”. Atuheire, a hard charging political operator with the FDC, says Besigye never minds election losses but rather is concerned by the “subjugation” of the masses.

“He’s a very silent man. You can move with him from here to Gulu without him saying anything. He speaks a lot publicly when it matters,” says Atuheire also known as Unstoppable.

Atuheire says Besigye made the right call about the next election. “I did not want him to run in 2016. He can fight in other ways.”

He says Besigye’s main pre-occupation is “liberation” and motivating other Ugandans to fight for what is right. “Through his mentorship, I have learnt a lot. I will go and make my mark as a person.” Atuheire tells Leo Africa Review in an interview.

“People thought Besigye is leaving the scene but as you can see he is giving opinions on Covid19 and what not.”

The Besigye wave saw some ‘young Turks’ join FDC in the murky world of opposition politics. Moses Byamugisha, Brian Katana, Onghwens Kisangala, Gloria Paga all joined the struggle one way or the other.

Besigye is very active on Twitter and once in a while will address a press conference on a topical issue.

As he mulls his options, Besigye is watching another major opposition candidate getting the same treatment he did: arrests, torture and derailment of party activities by a vengeful state. A young politician, Robert Kyagulanyi Sentamu aka Bobi Wine, at 38 is exactly half the age of President Yoweri Museveni and is taking up the mantle.

Bobi Wine is cut from a different cloth: a figure from the central region and a pop star; one could add he is Catholic. It remains to be seen how far he can go.

Taking part in elections was bemoaned by Besigye for what he called an unfair process controlled by his nemesis, President Museveni.

Besigye derided the Electoral Commission as ‘Museveni’s walking stick’. Matters were not helped by the body being headed by someone who led a prosecution against him in the infamous rape case which the state slapped on him after he returned from exile in 2005. He was acquitted in 2006 in what pundits described as one of the dirtiest ploys by the government against Besigye.

It is not clear what Besigye will do next but those who have followed his political career can’t see anything other than sustained political activism. For a man who demystified Museveni as an all-conquering General and held a mirror to the NRA modus operandi, few can say curtains are closing anytime soon on the Besigye chapter in Ugandan politics.

Editor’s Note: This article is a collaborative effort between Vox Populi and the LéO Africa Review