By Robert Madoi

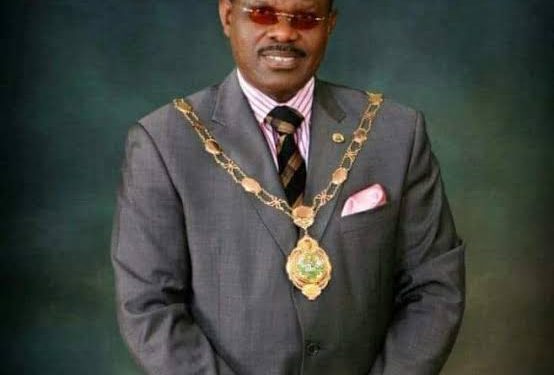

Nasser Ntege Ssebagala, the son of a greengrocer who appeared to have secured his reputation after he twice served as Kampala mayor, died on September 26th, aged 72. In their elemental theatricality, Kampala mayoral races have come to be exercises in raw power. Ssebagala, who was fatally knocked sideways by an intestinal complication on Saturday, run a campaign that permits no other conclusion but victory when Kampalans directly elected a mayor for the first time in 1998.

While his win — which took Kampala out of the hands of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) government — was anything but a feat that reflected luck, the victory lap didn’t last long. A brush with the law in the United States of America brought with it eight counts of fraud that looked primed to bludgeon him with bleakness. Although his acolytes back home preferred not to discuss this unpleasant possibility, the mayoral robes were duly handed to his sidekick (Sarah Nkonge).

Such was Ssebagala’s history — replete with absurdities and brilliances — that after serving his time, he returned home to much fanfare, pomp, and grandiosity in February of 2000. He was so dazzled by the theatre of it all that he thought running for the country’s top job in 2001 an achievable aspiration. It didn’t however, take long for Ssebagala to be considered an intriguing but enigmatic figure. To some, this was squarely down to the fact that — besides having a tenuous grip on the English language — he was lacking in all social graces.

Voice for the downtrodden

It could have also been that, in his hard eyes, a rare energy was beginning to emerge in Kizza Besigye. Hours after Ssebagala passed, the four-time presidential candidate tweeted thus: “Hajj Nasser Ssebagala was a good natured man, who wished others well. He was a witty, creative, courageous and charismatic leader. A leading and articulate voice of marginalised young people. Though he stumbled in later years, he’s left a big mark on Uganda’s liberation struggle.”

In 2001, Besigye, who had publicly disagreed with President Yoweri Museveni and ran against his ex-commander-in-Chief, exuded a seriousness and intensity that left many in the opposition ranks playing catch-up. Not Ssebagala though. A dearth of requisite academic qualifications however forced the man that came to be known as Seya to occupy a supporting role. Eminent figures in opposition politics soon thought him either too naive or eager to impress. Marginalised young people continued to eat out of his palms. They commanded blind obedience even when their man told them to rally behind Besigye.

Ssebagala met a less enthusiastic audience at the Democratic Party (DP), and consequently broke ranks with Uganda’s oldest political party before returning for a second stint as Kampala mayor in 2006. After winning the mayoral race, Ssebagala restored relations to their proper channels with DP. The open wound that was touched during an acrimonious DP presidential race with John Ssebaana Kizito healed. It didn’t take long for relations to once again reach breaking point. Ssebagala burst with indignation when Norbert Mao used his prodigious memory and smarts to convince DP delegates in 2010 that he would be meticulous in reviewing even the smallest details. In a terse statement, Mao paid “tribute to…Ssebagala for his business acumen which saw him rise to be one of Uganda’s most enterprising and successful businessmen.”

It is harsh to label Ssebagala as an underachiever or, as some have argued, a man of limited intelligence. Mao, who has bent every effort to enforce top-down rule in DP, described Ssebagala as a true champion of the downtrodden. Ssebagala’s humble beginnings effectively made sure that his relationship with the downtrodden wouldn’t be marked by formality and emotional distance. Although Ssebagala oftentimes became the object of withering criticism for his lack of sophistication, he wasn’t one known to have a penchant for feathering his own nest. Never mind that he once confessed he would “rather buy a suit for $3,000 than to buy 20 of $100.”

Rags to riches

From a young age, he learnt — or be it in a vague way — that hope and despair tend to live side by side. He grew up in a thatched hut on a sprawling piece of land in the Kampala suburb of Kisaasi where his parents had a vegetable garden. The produce that came out of the garden was vended from a stall in Nakasero. Ssebagala started helping out his father at the stall when he was a few months shy of turning eight. He counted the wife of the Cambridge-educated Governor of Uganda, Sir Andrew Cohen, amongst his clients. Ssebagala’s father also ensured that his son brushed up his knowledge of tenets of Islam in a madrasa in Wandegeya. The success at giving the first of his 27 children a formal education was limited thanks in no small part to financial hiccups.

Left with little choice, Ssebagala grew in the business of vending vegetables to the point that he wanted to see it climb correspondingly with demand. A car that could have been a solution to his tottering career as a salesman was out of reach. Since he lacked the inhibition of asking for favours, Ssebagala successfully sought out one of his maternal relatives. He then made the switch from vegetables to milk following the creation of Dairy Corporation by an Act of Parliament in 1967. Pleasantly surprised by the manner in which he networked energetically, Ssebagala’s bosses at the corporation sent him to Kenya to do a short course intended to smoothen out anything that looked rough around the edges.

Mafuta mingi or self-made?

By the time Ugandans were sharing the spoils after President Idi Amin expelled Asians, Ssebagala had already stepped down from a sales manager job. At that time nearly 20 million litres were being collected through a network of about 90 milk-collecting centres. Ssebagala though was convinced that it was the right time to move on. His judgment of the merits of starting a high-end accessory store off Kampala Road was astute. Ssebagala always insisted that he started the shop from scratch, but this didn’t stop people from labelling him a mafuta mingi.

A pejorative meant to capture the trappings of crony capitalism, the mafuta mingi were a new social class that sprouted from Amin’s nationalisation of Asian businesses in 1973. These unabashed beneficiaries of patronage were expected to supplant the most productive elements of Uganda’s capitalist and merchant classes. Critics charge that rather than install people of good work ethic, this dark chapter enmeshed Uganda in ‘short-termism’. Money became part of the national ethos, and a quick-fire way to the top of the pecking order. All of this compelled those that cherish the idea of sacrifice to endure such unmerited and at times humiliating torture.

Ssebagala though preferred to be seen less through the mafuta mingi lensand more through that of a self-made businessman. He might have been a semi-literate, but his visionary genius displayed itself through his successful establishment of a business empire. It’s this rags-to-riches backstory — street born as it was — that resonated with marginalised young people. To the elite, though, Ssebagala was the very embodiment of the ethical issues that were conspicuous during Amin’s era. The charges of making false statements, bank fraud, and transporting altered securities he was slapped with in the United States were very Amin-esque. It turns out that in death, as in life, Kampala’s first directly elected mayor continues to divide opinion.