By Dr. Stella Nyanzi

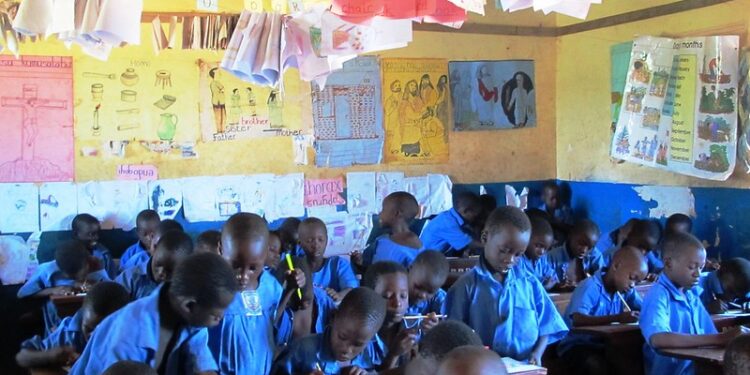

Although the 1995 Constitution of Uganda stipulates that, “No child shall be deprived by anybody of education for any reasons,” most Ugandan children have lacked education for almost two years. 16 months since the first COVID-19 lockdown, and Uganda’s children are effectively missing school. Although the education sector is headed by the ring-wife to President Yoweri Museveni, its most revealing indices of school attendance, retention of learners in school and consumer satisfaction – all have dismal scores. Although Mrs. Janet Kataaha Museveni, postures as the mother of the nation, and insists on her subordinates addressing her as Mama Janet, the minister of education and sports has not mothered Uganda’s children well enough when it comes to ensuring their sustained access to education in the pandemic. In addition to withholding education from the vast majority of Ugandans, the Ministry of Education’s inadequacies and excesses have ensured that the gap in access to schooling between the haves and have-nots is more accentuated than ever before. While the children of a few wealthy Ugandans continued with their classes through online school, children of poor citizens continue to miss out on their education because of many structural failings.

I analyse the important relationship between notions of ‘good parenting’ and ‘bad parenting’ on the one hand, and giving children access to education on the other hand. This analysis is foregrounded by international and national mandates that posture towards ensuring universal access to education for all children. Thereafter, I analyse the challenges of equitably educating children in the COVID-19 era in Uganda.

Education attainment is a key marker of progress in the world. The right to education is a fundamental human right that lays the foundations of reducing poverty, enhancing economic growth, skilling citizens to contribute towards developing their communities, promoting values of democracy, peace, tolerance and justice, among others. Good governments work hard to avail free or subsidized compulsory education to all children in the formative ages of six to 18 years, regardless of race, gender, ethnicity, religion, political party affiliation, income status, and rural or urban geographical location.

Since colonial days, in Uganda, going to school was a sign of civilization and modernity. Schooling – specifically the ability to read and write – distinguished between nominal village bumpkins and their colonized, civilized and christianised counterparts in society. So special was this colonial class of locales, that their elevated social status was even set part through the label “abasomi” translated from Luganda language to mean “the readers.” Education was an important prerequisite to joining the elite class of colonial administrative assistants delegated all over Uganda to manage subjects on behalf of the British Queen’s authority and power. Education was also the precursor to joining the professional class of clerks, artisans, and other service providers surfacing in pre-independence Uganda.

This combination of the universalist human right to education and the historical legacy of colonialism that elevated the value of schooling, still entrenches the importance of educating one’s children in Uganda today. For many parents of means, offering a good education to one’s children and other dependents is the most important symbol of good, successful and responsible parenting. It is the norm that, “good parents educate their children,” and inversely, “bad parents fail to educate their children.” Many adults spend the bulk of their productive years working hard to earn an income sufficient to educate their offspring in the best schools their money can afford. Several others take out huge loans from banks and money-lenders in order to pay tuition for their progeny. Some even go as far as selling family treasures including plots of land, animals, hard assets such as motor vehicles in order to afford the school fees of their children.

This deep desire to educate Uganda’s children echoes the national legal regime requiring the state to respect, fulfil, and protect the right to education. Article 30 of the Constitution of Uganda states that, “All persons have a right to education.” Furthermore, on the rights of children, Article 34(2) clarifies that, “A child is entitled to basic education which shall be the responsibility of the State and the parents of the child.” Moreover, Article 34(3) emphasizes that, “No child shall be deprived by any person of medical treatment, education or any other social or economic benefit by reason of religious or other beliefs.”

These constitutional provisions are further strengthened by several national policy frameworks including the Uganda National Program of Action for Children (UNPAC), the Children Statute (1996), the Education (pre-primary, primary and post-primary) Act (2008), the University and Other Tertiary Institutions Act (2001), the National Development Plan, the Education Sector Strategic Plan, etc. In addition, the government established national programs aimed at accessing affordable education to many more children in Uganda including the Universal Primary Education, and the Universal Secondary Education schemes of free public education. Privatisation of education allowed children with access to funding to attend private schools offering diverse syllabi including the Uganda national curriculum, American curriculum, Cambridge curriculum, and French education system.

Given this solid background, how is it possible that children have missed school for 16 months in Uganda?

On 18th March 2020, when President Museveni declared the first national lockdown of 32 days, he ordered for immediate closure of all government and private schools at all levels (including nursery, primary, secondary, college, university, tertiary institutions) of education. Major highways were clogged with traffic as parents and guardians rushed to evacuate their children from these institutions – particularly boarding schools where children spend up to three or four months per term or semester, respectively. 15 million children in Uganda experienced the abrupt disruption of their access to school-based education. While school proprietors, teachers, students, pupils and parents expected the halt in school attendance to be short-lived, unfortunately this has not been the case for most Ugandans who rely on physical attendance of school in order to study.

The COVID-19 pandemic saw Uganda’s technocrats populating the COVID-19 Taskforce advising the president to repeatedly renew the closure of all schools for many more months. As the severity of the pandemic reduced, some prohibitions were serially and partially lifted from some sectors in cascading style. However, schools remained firmly closed.

“I must protect my grandchildren from catching the virulent virus,” the militant father of the nation patronizingly declared when explaining the rationale of his war on COVID-19.

To bridge the prolonged gaps in accessing education during the national lockdown, the president envisioned that Uganda’s children would rely on technologies to access remote education, distance learning, off-site classes, or broadcast lessons. In subsequent presidential addresses to the nation during the lockdown, President Museveni progressively promised to distribute televisions, radios, and most recently internet-based classes to Uganda’s learners locked at home in order to stay safe from the virus.

In making these grandiose overtures, the father of the nation was perhaps out of touch and far removed from the infrastructural realities on the ground in most of Uganda. Broadcasting education lessons to diverse social classes attending varying levels of education would necessarily rely heavily on full-time access to electricity throughout the different topographical terrains of the country. Furthermore, this would require availability of a technological receptor (be it radio, television, smart phone, tablet, computer or other internet-friendly device) in all the households of school-going children. In addition, affordability of the internet despite the layers of exorbitant taxes and subscription costs of data was critical to accessing digital classes. Many rural areas in Uganda lack electricity. Poorer households often cannot afford the costs of electricity bills even when they are based in areas on the electricity grid. Power outages due to scheduled load shedding, broken cables or transformers, weather disruptions, natural disasters such as landslides or floods feature frequently on Uganda’s landscape.

Technological inequality manifest through the digital divide or gaps in internet access is a real indicator of social disparity between the privileged and under-privileged, powerful and powerless, haves and have-nots, urban and rural, male and female, literate and illiterate, etc. Children of poorer parents living in lower income households and attending under-resourced public schools lost education during the last 16 months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Uganda. This education inequity is exacerbated by the grotesque fact that children of wealthier parents continued receiving their education via online classes organized and delivered by well-paid teachers in a few private schools mainly in the capital city. This small select group of elite children never missed a school day, stayed on course with their syllabi, sat for regular tests and progressive examinations, got promoted to subsequent classes, and did not feel the severe pinch of the national closure of physical schools.

Schools were briefly reopened – first for candidate classes and later for all other classes, when the transmission of COVID-19 was estimated to have reduced to manageable numbers. However, no sooner had most schools reopened by Easter of 2021 than the infection rates skyrocketed again, leading to the second wave in Uganda. Schools were among the new epicenters of infection. On 7th June 2021, President Museveni declared a second national lockdown that opened the curtain to unprecedented rates of infections, hospitalization, deaths and grief.

Once again, all schools were abruptly closed leading to several children getting stranded overnight in congested up-country bus terminals and long-distance taxi parks, as they failed to get affordable public transport back home. The following day, children of wealthy parents in higher income households merely switched on their laptops, logged into their private school’s online education portals, and continued studying uninterrupted. These are children who can afford to address the first lady and Minister of Education as “Mama Janeti.” Meanwhile the children of poorer parents woke up in homes with neither electricity nor smartphones – their access to education interrupted until their government-funded schools are reopened. These children wonder whether Mama Janet is a good mother given that she failed to avail them with affordable accessible education. Alas, the conundrum of education inequity is exacerbated during COVID-19 lockdowns in Uganda!

Dr. Stella Nyanzi is a Ugandan human rights activist, poet, medical anthropologist, feminist, queer rights activist, and scholar of sexuality, family planning, and public health.