By: Dr. Ekwaro A. Obuku

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, Uganda made huge strides in key health outcomes since 1986 when President Museveni shot himself into power. The life expectancy at birth is now above 60 years, up from below 45 years due to the wrath of HIV/AIDS, maternal deaths have reduced from above 500 to less than 350 per 100,000 live births, which is still unacceptably high and there has been simultaneous reduction in child mortality and malaria in the recent past.

On the international scene, Uganda is renowned for conquering epidemics including Ebola, HIV/AIDS and other viruses. Uganda has done relatively well fighting COVID-19, with relatively no curve to talk about. Until recently, Uganda was outshining its East African neighbors having maintained a significantly lower burden with zero deaths from COVID-19. Thus far, of the estimated 250,000 tests we have carried out, less than 1,200 cases are of COVID-19. Yet, over 90% of them have recovered from supportive treatment in Uganda.

Key success factors in Uganda’s fight against COVID-19 have been focused leadership from the top, community mobilization and cooperation, substantial monetary investment, trusting professionals in science and above all raising awareness about SARS-CoV-2. Nurses, doctors and midwives, the media and the armed forces have been leading at the frontline. So committed were Ugandan healthcare professionals that 27 of us caught COVID-19.

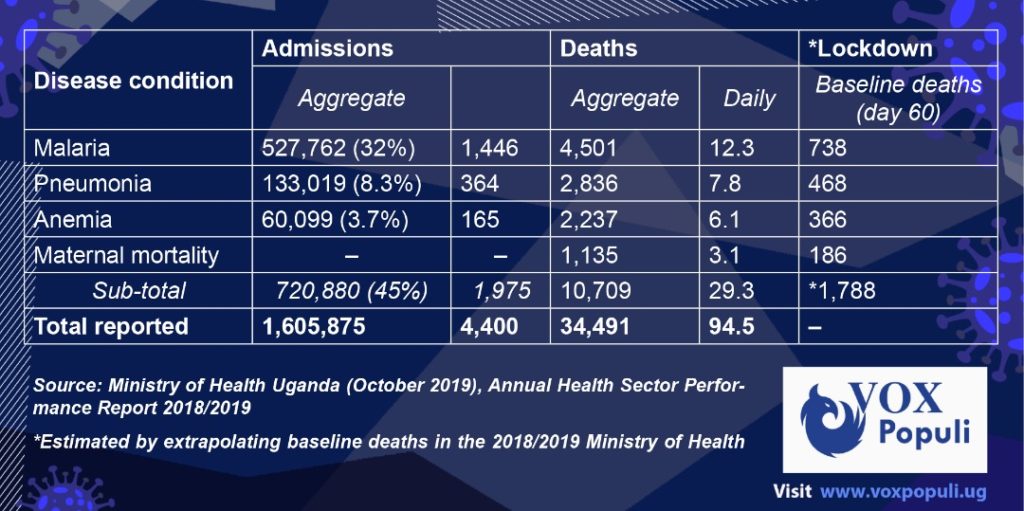

However, despite this early success, every policy intervention creates new policy problems. What are our blind spots? Are we covering all our bases in this COVID-19 fight? What has happened to the killer diseases prevalent before March 18, 2020 when Mr. Museveni declared 13 measures against COVID-19? A quick review of Uganda’s annual health sector performance report shows that severe malaria, severe pneumonia and severe anemia claimed over 10,000 lives in the 2018/2019 report. Further, there were 1,135 maternal deaths during this period.

Noteworthy, all these are premature and preventable deaths of Ugandans that were reported at health facility level. Mortality could even be higher if Ugandans who die in the community are captured in our district health information systems. A case in point are the recent deaths from sporadic cases of COVID-19 in the community. The blockbuster question is, are there excess deaths from severe malaria, severe pneumonia, severe anemia or pregnant mothers ever since we turned all our attention and resources to COVID-19? In his regular addresses to the nation, Mr. Museveni has been keen to point out each COVID-19 patient in such detail that Medical Ethicists would raise eyebrows and with satisfaction conclude, “Uganda’s COVID-19 curve is flat!” While no system is perfect, is the President receiving daily briefings on the non-COVID-19 curve?

Again, a quick review of the same 2018/19 Ministry of Health report suggests that Malaria, Pneumonia and Anemia contributed to 45% of all hospital admission in the 2018/2019 period. In addition, we lost an average of 12.3 Ugandans per day from malaria, 7.8 from pneumonia, 6.1 from anemia and 3.1 pregnant mothers during childbirth. Estimating this by day 60 of lockdown, we have 738 deaths from severe malaria, 468 from severe pneumonia, 366 from severe anemia and maternal deaths totaling over 1,788. Two issues arise from this 1,788 deaths figure; first that these Ugandans would have died anyway with or without COVID-19. The COVID-19 Scientific Advisory Committee could easily settle this question by reviewing the Ministry’s health management information systems monthly reports of 2020. Secondly, is the moral and ethical question, whether these deaths are any less important than the COVID-19 deaths of which Uganda has reported less than 10 in four months! It is this last matter that Mr. Museveni and his team ought to address if indeed all Ugandan lives matter!

Why has it taken Uganda four months to record its first COVID-19 death? The reasons are varied. The most obvious is that we simply missed them. Looking back, French scientists recently traced COVID-19 among patients who died from pneumonia-like illnesses in December 2019, in Paris. In Uganda, several travelers from Dubai during the 2019 Christmas season recall returning with “a very serious flu”. This retrospective evidence suggests the novel Corona virus may have spread globally earlier than estimated.

Noteworthy, Uganda’s Health Ministry has focused on travel history as a cardinal feature to identify potential cases of COVID-19. In so doing, the low hanging fruit of patients of respiratory diseases outside the border points of entry were given less attention. It is no wonder that recent cases of COVID-19 were initially treated as pneumonia or tuberculosis. Even so, testing SARS-CoV-2 doesn’t imply a disease process. In the event of widespread infection (high baseline risk), the likely occurrence of COVID-19 being diagnosed as comorbidity would be incidental.

The centralized COVID-19 screening, testing and treatment approach by the Ministry of Health has excluded key population groups. Despite the low catchment of COVID-19 positive cases (low test positivity rate) suggesting a high testing index, the first four COVID-19 deaths occurred outside the Ministry of Health COVID-19 control framework. Contrary to Sustainable Development Goal number 17 on partnership, the working assumptions of the Ministry left out private laboratories and medical centers. Yet, the health seeking behavior for the initial most-at-risk populations (international travellers and truck drivers) would likely first visit a private facility. It is therefore welcome news that the Ministry accredited MBN laboratories, a private entity, to conduct COVID-19 testing. Previously only the Uganda Virus Research Institute and Makerere University were doing so, reducing the efficiency of turn-around-times and limiting access to COVID-19 tests to the general public. This argument makes sense given the concerns of quality assurance for a new testing protocol for the novel Corona virus and anticipated high costs of $65 per test. Testing sites have been tripled as MBN laboratories have 7 branches countrywide in Arua, Gulu, Lira, Jinja, Mbale, Mbarara and Kampala.

What are our national priorities?

Although COVID-19 is has claimed only four lives in Uganda; beneath still river waters lurk crocodiles. Needless to say, our Parliament crowned the COVID-19 response with at least 300 billion shillings. Overall, over Shillings 2.8 trillion was released as supplementary budgets for COVID-19. Needless to say, this is the total budget request for the Ministry for Health for 2020-2021 fiscal year. Comparatively, by April 2018 about 360 billion shillings was required for Mass Action Against Malaria (Malaria Fund) to spray all districts in Uganda. This local funding has never come! Yet, malaria caused half a million admissions in hospital and killed 4,500 Ugandans according to the Ministry of Health 2018/19 annual performance report.

Likewise, if we invested in resilient national ambulance systems for the real killers: maternal deaths or road traffic accidents, would we not be more prepared for COVID-19? These ambulances would smoothly transport pregnant mothers before, during and after lockdown. In addition, Prof. Richard Idro the President Uganda Medical Association has recommended establishing the more efficient High Dependency Units (HDUs) in all district referral hospitals instead of Intensive Care Units (ICUs), whose patient outcomes are generally poor. In the end, implementing “what works” solutions lies in the hands of our political and civic leaders to whom we have entrusted a substantial proportion of our national treasury in the name of COVID-19.

Dr. Ekwaro A. Obuku, MB CHB, MSC clinical trials, FICRS-F is the former president of Uganda Medical Association.

Email: ekwaro@gmail.com

Twitter: @ekwarooobuku