The Covid-19 pandemic has thrown Uganda’s economy into a tailspin and disrupted supply routes both at the domestic and international routes. Product sales of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) have cratered and job culls have left thousands without employment as banks have foreclosed on a number of properties which have been sold at the fall of the hammer.

As governments directly intervene to shore up fragile economies, there is an emerging school of thought that the neo-classical capitalist state may no longer be tenable.

This, according to the exponents of the view, requires government to shift from enforcing a policy role to playing a direct role, alongside fiscal prudence and tough austerity measures to resuscitate the economy from a recession. Others suggest that the state should sustain a hybrid model involving government and the private sector.

During lockdowns, a number of capitalist states in the West directly intervened by doling out stimuli to the citizenry.

Abubakar Mayanja, a financial economics expert postulates that direct intervention through stimuli is a precedent in advanced economies, “However, the interventions are within the mandate of governments through expenditure increases, liquidity easing and asset buy backs by central banks. The circumstances of the economies are different, some have the fiscal flexibility to increase expenditure while others don’t; at the end of the day the two options lie in fiscal and monetary interventions.”

Perhaps this could be an opportunity to reexamine the stringent neo-liberal policies the Ugandan government adopted in the early 1980s and 1990s.

A book released in 2019 entitled ‘The Dynamics of Neoliberal Transformation’, authored by American academic Giuliano Martiniello, an associate professor at the American university of Beirut, argues that neo-liberal policies in Uganda left out the poor.

“While Uganda is having a fast-growing economy [averaging over 6% a year], it is benefiting only a few politicians who have access to money and resources. The poor are left out of this growth,” Martiniello noted.

He argues that the economic growth rate couldn’t continue to be cited as an achievement when the masses in rural areas and urban poor suffer from mal-nutrition, food insecurity, unemployment and poverty.

He singled out the privatisation of social welfare services through initiatives that emphasised public-private partnerships (PPP) as a problem.

“The government reduced public funding due to this strategy [PPP] and dropped many of its responsibilities and replaced its role with private sector contracting for social provision. This has increased socioeconomic and spatial inequalities across classes among different regions of the country, and across the urban/rural divide,” the author said.

A number of vital sectors like Uganda Commercial Bank (UCB), Uganda Airlines and Uganda Railways Corporation were privatised in deals that were tainted with corruption.

In the place of government-owned commercial banks today are multi-national banks and companies that expatriate most of their profits to safe havens and secrecy jurisdictions.

But the recent recapitalisation of Uganda Development Bank (UDB) to a tune of one trillion shillings perhaps suggests a paradigm shift in government’s thinking.

The Finance minister, Matia Kasaija, told Vox Populi that government is intervening by deliberately giving credit to limping businesses and paying debts.

“Our intention is to leave businesses and even individuals by giving either credit or if we owe money to individual companies and we think we should pay that money out so that it goes to augment capital flows of companies and individuals. Loans are being restructured, we have bought food for the vulnerable,” he argued.

The Director for Economic Affairs in the Finance ministry, Moses Kaggwa says the Covid-19 pandemic has spawned a re-think in government intervention.

“UDB was revived and it has intervened in a lot of companies, Atiak Sugar Works, Soroti Fruit Factory, the salt project in Kasese, are all part of the intervention. Uganda Airlines came back. We are reviving UDB to curb interest rates, it’s something we are mooting and it is starting to happen. Because there are areas we believe the private sector may not be able to intervene at the very beginning and we said let government put its resources there,” argues Kaggwa.

Whereas countries need to rely on Foreign Direct Investment, this must be dovetailed with exports.

Abubakar Mayanja argues for a meaningful strategy to provide a platform that connects ordinary Ugandans to global value chains through exports and specific productive sectors so that growth is inclusive from the bottom.

“Only a few people can be employed in transport and banking. However, Coffee, Fish, Tea and other export oriented-value chains whose markets are unlimited can gainfully employ millions and increase fiscal revenues and reduce the macroeconomic vulnerabilities emanating as a result of weak exports that account for a deficit,” argued Mayanja.

The focus he says, should be on having a level playing field and an excellent business environment free of corruption and patronage that does not favour foreign or domestic capital.

To revitalise the economy, there is need for businesses to access Capital both of an Equity and Debt Nature (UDB), revise Capital Gains Tax for Private Equity Firms that trade in shares of companies, concentrate and develop sectors linked to global value chains by developing special economic zones that focus on export markets, argues Mayanja.

Government perhaps needs to revise the monetary policy to increase local savings and capital formation, such as allowances on property and mortgages and revise the tax code especially income taxes to incentivise SMEs battered by the Covid-19 pandemic.

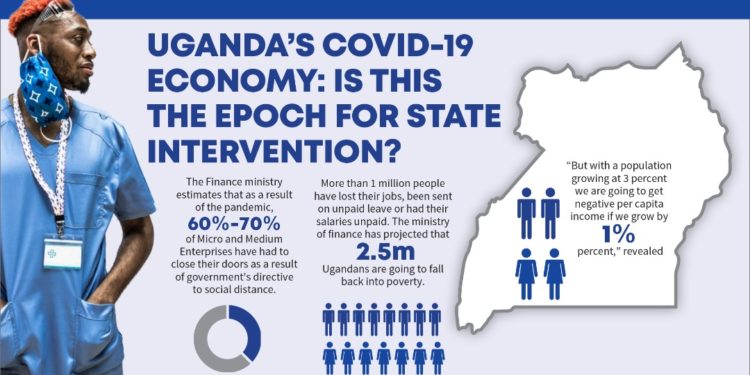

The Finance ministry estimates that as a result of the pandemic, 60%-70% of Micro and Medium Enterprises have had to close their doors as a result of government’s directive to social distance. More than 1 million people have lost their jobs, been sent on unpaid leave or had their salaries unpaid. The ministry of finance has projected that 2.5 million Ugandans are going to fall back into poverty.

It has become imperative for government to revise its economic strategy to better suit and manage the repercussions of COVID-19 on our economy.

Corti Paul Lakuma, a macro-economic expert at the Economic Policy Research Centre (EPRC) says propping up the role of the state is the way to go.

“But this is easier said than done. Therefore, I call for pragmatism. This is the principle of what works in the context of available capacities and resources. If something is best done by the state, then the state should do it. Equally, if something is best done by the private sector, the government has no business in it. Then there are mixed scenarios where the state works with the private sector,” opines Lakuma.

For instance, Lakuma says government performed well in the provision of water, health services, and the provident fund amongst others. “Those areas should be left to the state. Equally, the private sector has done very well in bridging the gap in education services and we should encourage that going forward. Also, there have been viable public and private partnerships in power generation sector. We cannot abandon that for a pure statist approach.”

Governments are currently stretched and many in sub-Saharan Africa will register negative growth rates. The state may not be able to sustain funding to vital sectors and this may require partnerships to mobilise resources.

The Secretary to the Treasury & Permanent Secretary in the Finance Ministry, Keith Muhakanizi told Vox Populi in an interview that Uganda’s economy will likely grow by one percent, which is in a much better position, compared to other African economies.

“But with a population growing at 3 percent we are going to get negative per capita income if we grow by 1 percent,” revealed Muhakanizi.

Muhakanizi, an exponent of a lean government, says there is need to revisit public expenditure.

“We have put out a number of mechanisms, stimulus packages, the economy got destroyed when aggregate demand of the economy was destroyed, so how do we get aggregate demand going? Of course that is through public expenditure.” Said Muhakanizi.

He says that this is what compelled the government to capitalise UDB so that enterprises can borrow to increase aggregate demand through exports.

Muhakanizi says technocrats have enforced prudent measures.

“We put in place macro-economic management measures and the exchange rate has been managed, inflation has remained low and thanks to the good weather food has been available.”

On Tuesday, October 20, 2020, the minister of state for Finance, David Bahati tabled a shs 6.2 trillion budget to plug a deficit in this financial year’s budget. Government plans to borrow this money from the domestic market and the International Monetary Fund. (IMF).

But Uganda’s debt portfolio is worrying.

The country’s debt stock grew from Shs.46.36trillion at the end of June 2019 to Shs. 48.91trillion at the end of December 2019.

Of this, external debt was Shs. 31.53trillion representing 64 percent while domestic debt was Shs. 17.38trillion representing 36 percent. This represents an increase in nominal debt to GDP from 36.1% in June 2019 to 36.97% in December 2019.

There are fears that overreliance on domestic borrowing crowds out private sector investments by hiking the cost of borrowing since government consumes a huge chunk of loanable funds from commercial banks.

Uganda’s expenditure growth has consistently outpaced growth in revenue collection, creating a widening financing gap and putting Uganda at risk of debt distress. Increasing debt also ties up resources in interest payments – domestic interest payments are now the third largest item in the annual proposed budget FY2020/2021 at shs 4trillion, which is equivalent to 11.3 percent.

With the price of the barrel of oil on the international market plummeting, there are fears that Uganda, which had hedged its bet on oil production, could default in paying the loans and attract less foreign direct investments.

Monetary Policy Interventions

Mandatory debt restructuring for affected sectors and nationally

Unlimited balance sheet and liquidity support through Repos and Reverse Repos

Consider Central Bank Digital Currency to increase velocity of UGX globally and regionally; increase fintech traditional banking integration

Stress test banks now to have a better picture of financial stability and mitigate systemic risk

Re-examine the optimal monetary supply with a view to increased quantitative easing

Fiscal Policy Interventions

Re-balance expenditure from other sectors to the health sectors and import substitution in the food and health sectors, as a corollary, add export industries to the essential list for expenditure allocation to maintain FX inflow

Draw on the National Emergency Fund

-Rationalise payroll tax thresholds for vulnerable and or low wage medical and allied staff.

-Offer incentives to private hospitals to increase ICU and treatment capacity.

-Support as an emergency, local efforts to produce ventilators, respirators, reagents and swabs; prioritise funding to other local manufacturing and job focused enterprises in a post COVID19 world – capitalise and use existing capital vehicles such as UDC and UDB, the innovation fund at Ministry of Science Technology and Innovation (MOSTI).

-Cut the size of government to reduce recurrent expenditure, merge related agencies for efficiency, government restructuring to re-consider budget items such as Public Sector Management and Public Sector Administration.

Pay all domestic arrears

-Budget to prioritise the food industry, health, logistics and supply chain; prioritise allocation to agriculture and further processing.

-Reduce the rate on the Agriculture Credit Facility (ACF) and allow more financing for agriculture machinery and restructure the Agriculture Credit Facility (ACF) to invest directly and take more risk.

Private Sector Intervention

-Provide technology to, among others, ensure real time and geo-referenced monitoring and management of the COVID-19 pandemic.

-Ensure supply of key health equipment and supply chains, increase healthcare systems’ capacity through local manufacturing (sanitisers, reagents, ventilators and respirators, testing kits).

-Ensure food provision and supply chains are functioning, deep and competitive.

-Lead the transition from analog to digital platforms across sectors, but for now with a focus on ensuring continued ability for daily wage earners and the trader/merchant class to keep economically active; unlock inventory through access to local and global markets, supply chains and financing.