BY PATRICK LANG’AT

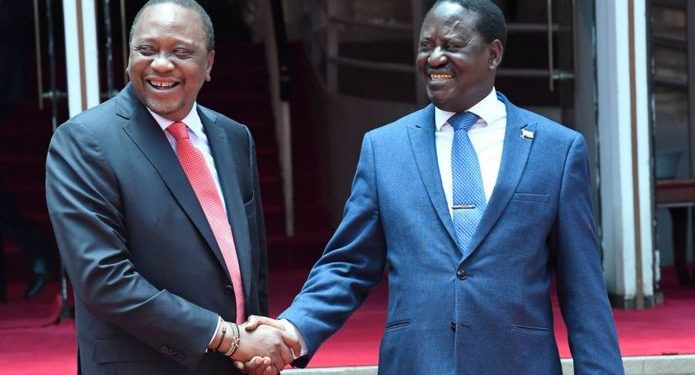

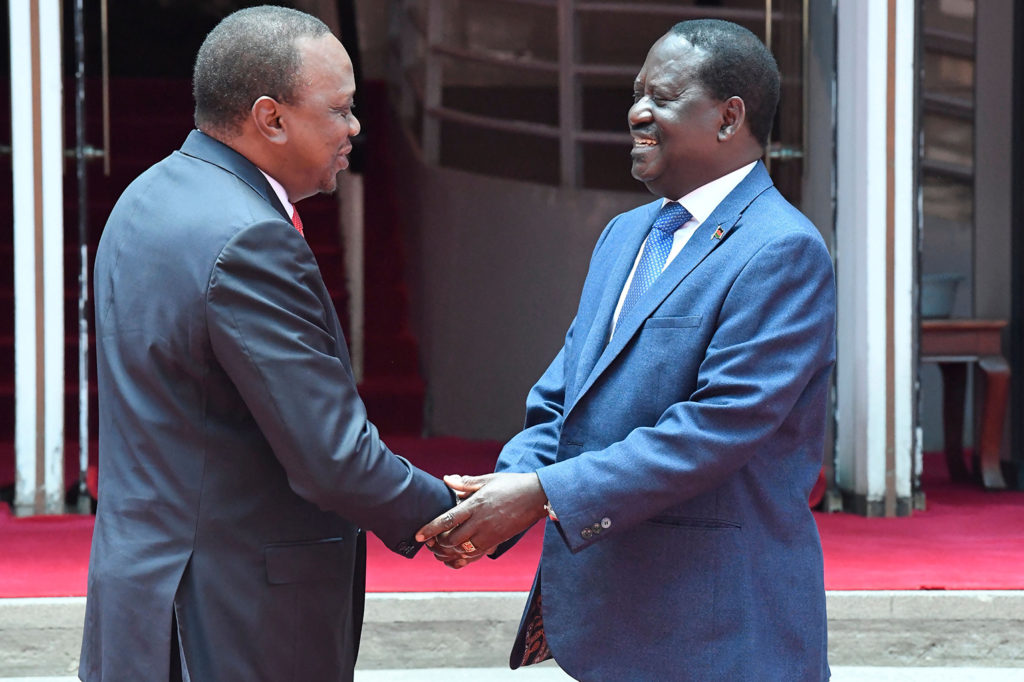

On March 9, 2018, Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta and opposition leader Raila Odinga shook hands on the steps of Harambee House — which houses the President’s office — kickstarting a storm that has led to one of the most consequential political moments in recent Kenyan history.

The handshake came after months of push-and-pull between the opposition and the government following two highly controversial presidential elections in 2017, the first of which (won by Kenyatta) was nullified by the Chief Justice David Maraga-led Supreme Court citing irregularities.

It was the first time in African history, and only the fourth time in the world, that a court had annulled a ruling President’s election victory.

But instead of participating in the rerun, Mr Odinga pulled out, citing a failure to implement the opposition’s “irreducible minimums” including electoral reforms and compensation for those affected in the post-election aftermath.

Instead, he formed a ‘National Resistance Movement’ with the aim of advancing electoral justice in Kenya and threatened to collect their own taxes in counties they controlled or had the majority support.

The resistance escalated on January 30, 2018, when Mr Odinga took an oath as the “people’s president”, adapting the oath his opponent took three months before to declare himself the president of the people.

It was a surprise, therefore, when the two “sworn enemies” shook hands on March 9, 2018 and vowed to build bridges—leading to the famous Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) — moment that has completely altered Kenya’s political arena and is now on the brink of altering its constitutional dispensation.

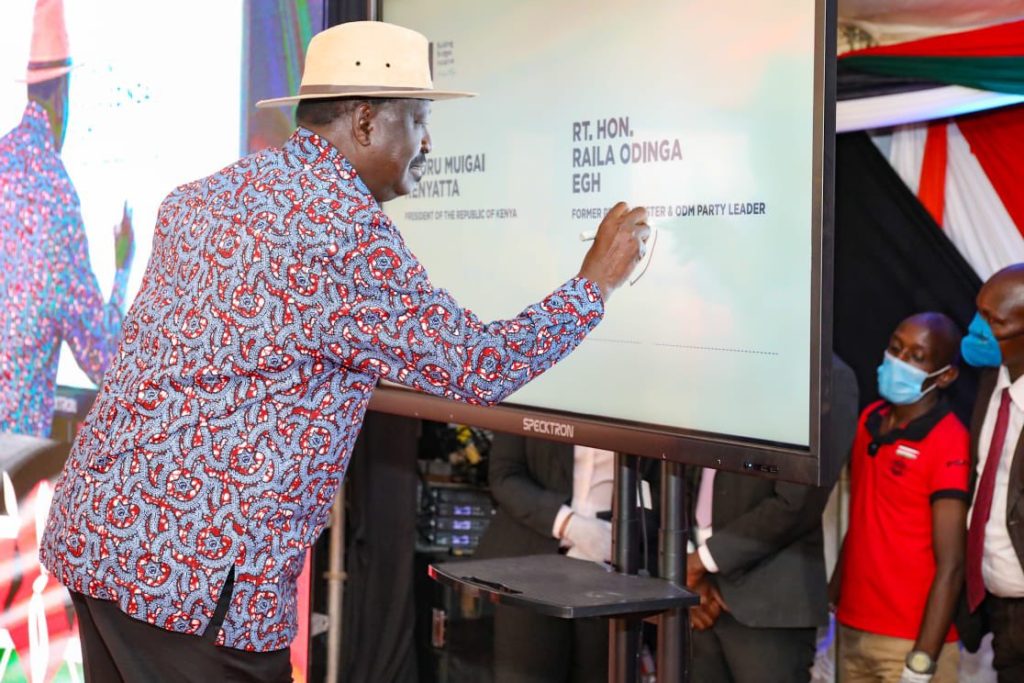

On October 26, 2020, President Kenyatta launched a report seeking to amend various parts of the Kenyan Constitution. Both the president and Mr Odinga believe it contains solutions to Kenya’s problems of political inclusivity, electoral injustice and will lead to greater shared prosperity.

The BBI report has proposed the re-introduction of the Prime Minister’s post, a presidential appointee approved by the National Assembly, who will be the leader of government business in the House.

The Prime Minister will supervise the execution of functions of ministries and government departments as well as chair cabinet meetings as assigned by the President.

The President, the BBI report says, will make the first nomination, and if rejected, the majority party or coalition will have seven days within which to nominate another person, who, if rejected, will give the President a free hand in the third nomination.

“If the National Assembly fails to confirm the appointment of the person proposed by the largest party or coalition of parties after the House fails to confirm the appointment of a person nominated by the President, the President shall appoint a member who, in the President’s opinion, is able to command the confidence of the National Assembly,” the BBI report states.

But it is not only the process of appointment of the Prime Minister that has raised questions.

Analysts have also questioned what the requirement to pick the Prime Minister from the largest party or coalition of parties means in a scenario where the President—who is supposed to make the nomination to be approved by the National Assembly—fails to get the majority of the House.

This might lead to a scenario where the President is then forced to enter into a France-like scenario where the President of a party who has not won the majority has to “cohabitate” with the party with the majority, who are then allowed to name their Prime Minister.

There will also be two Deputy Prime Ministers chosen from among Cabinet ministers.

There is also a proposition for the re-introduction of the Leader of Official Opposition – a post that was scrapped in the 2010 Constitution after Kenyans voted for a purely presidential system where the winner takes all – a situation that both President Kenyatta and Mr Odinga believe is responsible for many of Kenya’s unending political problems.

The Leader of Official Opposition, the BBI report says, shall be the person who receives the second highest number of votes in a presidential election, and shall sit in the National Assembly.

But there is a catch. The position will not simply be a shoo-in for the second placed candidate in the presidential poll.

The BBI amendment sets a caveat that the person has to have gotten at least twenty-five percent of all the members of the National Assembly. The report leaves a grey area as it does not say what happens if the runner-up fails to meet this threshold.

The order of precedence in the National Assembly shall be the Speaker, the Prime Minister and the Leader of Official Opposition—giving prominence to the latter’s office in the BBI’s bid to address the issue of inclusivity.

On the judiciary, the BBI team has proposed the introduction of the Office of the Judiciary Ombudsman, a presidential appointee who will sit in the Judicial Service Commission.

What is fundamentally different in the office is that it appears to give a presidential appointee exclusive decision making on the reprimanding of judicial officials.

“The Judiciary Ombudsman shall prepare regular reports to the JSC on any complaint which shall state the findings of the Judiciary Ombudsman; and recommendations on the action to be taken by the JSC,” the BBI report says.

Some analysts have read this as giving the Judiciary Ombudsman powers to reject complaints before it gets to the JSC—a body chaired by the Chief Justice and having representatives from the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, the High Court, the Magistrate’s court and two from the Law Society of Kenya—and seen to entrench the idea of judicial independence.

The Judiciary Ombudsman, who should have the qualifications of a Supreme Court judge, shall serve a single five-year term and will not be eligible for re-appointment.

On the police service, the BBI report has proposed the creation of the Kenya Police Council, which will be responsible for the “overall policy, control and supervision” of the police.

The Kenya Police Council, the BBI report states, will be chaired the Interior Cabinet minister, the Inspector General of Police, two senior members of the service appointed by the President, and the Interior Principal Secretary—all direct appointees of the Head of State.

The BBI report recommends the disbandment of the National Police Service Commission, which currently manages recruitment, vetting, and other human resources aspects of the police.

In what has been lauded as important progress, the BBI report elevates the Independent Policing Oversight Commission, now operating as an authority, into a constitutional commission with the protection of Chapter 15, meaning its members have security of tenure and are insulated from executive influence unlike other executive bodies.

The body is tasked with investigating and prosecuting cases of police misconduct, extrajudicial killings, and acts as the civilian disciplinarian of the police service.

Enough of the proposals in the document.

As it stands, the political class is headed for a clash, with President Kenyatta and Mr Odinga both pushing for the document to be voted for in a referendum, with no changes.

Deputy President William Ruto, however, is by far the biggest casualty of the handshake between his boss and Mr Odinga. He believes it is a way to block his 2022 presidential run and has called for a further discussion on the document, supported by Amani National Congress (ANC) leader Musalia Mudavadi and outspoken Narc Kenya party leader Martha Karua.

Those calling for the amendment of the proposals before a referendum also include the pastoralists community in Kenya—10 million people living in 15 counties with 109 constituencies and representing a staggering 80 per cent of Kenya’s land mass. They see the document as a continuation of the marginalisation they have faced for years.

Specifically, the pastoralists are angered by the provision in the BBI report that the revenue allocation will be on the basis of population, and not on the land mass provision that would favour them. Their argument is that the provision of service in an area where residents are scattered, like they are in pastoralists group, should also be considered in the distribution of revenue.

For Dr Ruto, the ambitious deputy president, opposition against the BBI is centered on three key issues. He questions the provision that a few parliamentary political parties be involved in the naming of electoral commissioners; the provision that the President appoints a Judiciary Ombudsman with almost exclusive say on the reprimanding of judicial officials; the provision to deny the Senate, born to protect devolution, final say in the division of revenue between the national and county governments.

Despite Vice President Ruto’s objections, those who support President Kenyatta and Mr Odinga want the referendum on the BBI proposals to happen as soon as possible—and with no further amendments to the document.

A draft plan by the team shows that they intend to collect the required one million signatures across the country in one month, with the electoral commission given another month to verify them to ensure that all those who have signed are registered voters. If satisfied that at least a million of the submitted signatures and details are of genuine voters, the electoral agency is required to submit the draft Referendum Bill which will accompany the signatures to the 47 county assemblies. If at least half (24) pass it, it then goes to Parliament – first the National Assembly and then the Senate, for concurrence.

The decision of the county assemblies is crucial as if more than half oppose the Bill, it dies there and then. Careful to win the county assemblies, the BBI proponents have sweetened the deal by introducing a Ward Development Fund to be managed by Ward Representatives—and pegged at five per cent of the total development budget of the county—in each of Kenya’s 1,450 wards.

“A proposed amendment to this Constitution shall be enacted and approved by a referendum, if the amendment relates to any of the following matters: the supremacy of this Constitution; the territory of Kenya; the sovereignty of the people; the national values and principles of governance; the Bill of Rights; the term of office of the President; the independence of the Judiciary and the commissions and independent offices to which Chapter Fifteen applies; the functions of Parliament; the objects, principles and structure of devolved government; or the provisions of this Chapter,” Article 255 of the Constitution of Kenya (2010) says—setting out articles on which Kenyans’ views must be sought in a referendum.

While those backing the BBI wholesale say the Bill should go to the people as is, those of a contrary opinion say the better route would be to iron out the contentious issues and have a “non-contested referendum.”

Caught in between are Kenyans, most of whom have not read the BBI document, and who, in the political noise, are not aware what the political divisions mean for them, and what that decision means for their future.

And as Kenya heads to another election in August 2022—where President Kenyatta will not be eligible to run, Dr Ruto will have the first stab at the State House contest with Mr Odinga expected to throw probably his last shot at the seat that has eluded him in his illustrious political career — all eyes are on the BBI.

For Dr Ruto, it is a big gamble. A push to oppose the referendum means risking defeat with monumental, almost suicidal, consequences to his 2022 presidential bid.

But with those backing the BBI adamant that no more changes should be made to the report before it heads to a referendum, Dr Ruto is now caught between a rock and a hard place: How do you convince your followers to back a document whose proposals you have criticised if the Uhuru-Raila side refuses to budge on the amendments?

The EAC, the region, and Africa

So, besides the political, legal and administrative consequences in Kenya, what is in it for the region and the continent at large?

Regarding the East African Community, the BBI report wants Kenya to forge even stronger ties with her neighbours, including the ultimate, yet elusive, dream of an East African Federation.

“This Constitution embraces the goals of African unity and the political confederation of the eastern Africa region as integral towards attainment of sustainable development, prosperity for all and stability,” the BBI report reads.

The state, the report directs, shall take legislative, policy and other measures to give effect to the dream of a united, politically powerful East Africa.

Careful not to lose the gains should the BBI report be adopted in a referendum, the team has suggested articles to ensure the formal inclusion of Kenya’s dream of regional integration into its supreme document—the Constitution.

The addition of an article specifically indicating Kenya’s support for the EAC and African Unity—championed by the EAC and the African Union, respectively—is the country’s boldest attempt yet to shield these foreign policy aspirations from possible future interference by office holders.

What next?

Political commentators will be keen to observe how this matter develops in the coming months, but, in the end, it all boils down to three men: President Kenyatta, Mr Odinga, and Dr Ruto.

President Kenyatta because, if the unamended Bill passes the referendum, he will have increased his say in the 2022 succession contest.

Mr Odinga because the BBI report could be the missing link in his elusive State House run.

For Dr Ruto, it is a double-edged sword: If, in the unlikely event, he manages to mount an effective opposition and defeats the BBI process in a referendum, his 2022 run is as good as won.

It gets tricky, however, if he goes ahead with this strategy and loses.

For him, there is the third possibility. He could jump ship and support the BBI process, push it through in a referendum and use it as his launching pad for 2022.

Whichever way it goes, there is no doubt in anyone’s mind that the BBI process might be the most consequential political engagement pre-2022 presidential elections.

Mr Lang’at is a 2019 Master’s in Journalism KAS Scholar at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, and writes on politics in Kenya.