The Uganda Communications Commission (UCC) is at it again. Like a troublesome child, UCC has its way around courting controversy, picking fights and quarrels every so often and, in a somewhat strange way, getting away with so much. It is noticeable that UCC’s altercations with the public are blind to who is at its helm. Here, the institutional transcends the individual, the state in its faceless and amorphous nature lays itself bare. In classic Shakespearean philosophy as enunciated by Jacques in ‘As You Like It’, “all the world’s a stage and all the men and women merely players; they have their exits and their entrances.”

When Godfrey Mutabazi was its executive director, he bore the brunt of public disapproval with the commission’s actions, including the freezing of internet activity in the 2016 general election. Mutabazi came off as the bad boy in the room, as a hard-nosed regime operative out to maul anyone crossing the government’s path. Was he? Was he not? Shakespeare teaches us that he only acted his part of the script, exited the stage and in entered Irene Sewankambo. Unlike Mutabazi who could tell a fat lie through the skin of his teeth and smile at himself while looking at one through the rim of his spectacles, quite shrewd with a tinge of arrogance, his predecessor is more likeable, even from a distance; Irene has a baby-face smile and can look serious, talk tough without coming off as a bullish rogue. That has disarming power. Their character juxtaposition aside, UCC’s altercations with the public and media are deeply entrenched in the institutional psyche and the individual, regardless of who they are, is but an actor in the Shakespearean stage (and sense) of life.

That point is important to make because it is an ingredient for analysis of the psyche of the Ugandan state in terms of media regulation. In there, one realizes the futility of focusing the gun butt on the heads of these executive directors who are merely actors on a stage. It is relieving and liberating at the same time because it forces us to interrogate the structural issues abound that feed into the never-ending contradictions and confrontations between the state and the media in Uganda. But even beyond this institutional versus the individual dichotomy, there is power in history, pre- and post-colonial history, a power that nourishes our appreciation of the media-state relationship as well as the role and place of the superstructure in this maze. Why do things happen the way they do? Why is it that the more they change the more they remain the same? Here, sentiment wanes, analysis starts.

When UCC sneezes everyone catches Covid-19

So, UCC issued a directive demanding for the registration of news websites and online broadcasters, requiring all providers of such services to register by October 5, 2020. The directive affects services such as blogs, online televisions, online radios, online newspapers, internet-based radios and TV stations, streaming radio and TV providers, and video-on-demand providers.

I read an article published on September 9, 2020 by the African Center for Media Excellence (ACME) on its website authored by Raymond Mpubani and Clare Muhindo. The weekend after that article was published I listened to a quite informative and animated debate between my classmate at the Law Development Center and now colleague in the legal profession, Ivan Bwowe and UCC’s Waiswa Abdul Sallam, the Head of Legal Affairs, on 93.3 KFM’s VPN show hosted by Ben Mwine. A lawyer working with one of the non-governmental organisations had asked me to join a press conference at which UCC was the subject of bashing (not sure if the presser happened) and later a court petition lodged by Bwowe. Shortly after that I read an article by the Nation Media Group (Uganda)’s General Manager Editorial, Daniel Kalinaki in his Daily Monitor column, that was followed by an exchange on Twitter with UCC that raised pretty important points. I agree with Kalinaki’s clever arguments and those advanced by Mpubani and Muhindo in their articles. It is my considered view however, that they miss the point, bigly and I hope I am wrong.

Firstly, I am affected by UCC’s actions because I am part of the East African Center for Investigative Reporting which publishes the online publication www.voxpopuli.ug. I am also, as someone trained in media law, often handling matters for clients in this space and so, in more ways than one, UCC’s actions affect me both as a publisher, entrepreneur and practising lawyer. I will, however, decline the invitation to join the crowd to crucify UCC. It is not that I approve of their latest directives which, as Mpubani noted in his article, aren’t coming for the firs time. There is everything wrong with those directives as Kalinaki has ably articulated in his column and Twitter chat with UCC and Bwowe ably voiced out on KFM’s show.

If you ask me however, and this forms the basis of departure with the ‘crucifixion crowd,’ there is one fundamental flaw with all these shades of opinion and it goes to the root of the problem of media regulation in Uganda. Firstly, for a country in puberty stages of democratisation, we expect too much of the state and hope that by preaching good manners to it, it will somehow see the logic and act better. Sometimes that works. Bernard Tabaire and others before and after him, has captured the history of state harassment of the media in his 2007 treatise, “The Press and Political Repression in Uganda: Back to the Future?”. In there, one appreciates that the more governments in Uganda change, the more their relationship with the media (in large part) remains the same.

And so, for as long as we are still bearing the pangs of nourishing our democracy project (and it is work in progress that takes centuries), the state versus the media confrontation will remain a prominent feature of this abusive relationship. It matters not if we have constitutional petitions in the Supreme Court such as the landmark Andrew Mwenda and Charles Obbo Vs. Attorney General case or constitutional provisions guaranteeing freedom of the press. The practice, as opposed to the edicts of the law, is a more often important measure of progress. The law can and often does say one thing and in practice the actions mean another. This is an age-old debate on the place of the law in the political arena, what in jurisprudence scholarship is called instrumentality versus instrumentalisation of the law.

So, first, I have managed expectations to the extent that try hard as we might to push back, how much progress we register can only be in tandem with the wider, structural political context of the country. One can say this about several other freedoms and rights.

But why regulate the media?

If I have not done that (expectations management) successfully, I hope that in the second limb of this essay, I can speak to the ideological basis (which UCC does not seem to articulate well and which its critics barely pay attention to) for media regulation. Once that is done, I shall then delve into the crisis of media regulation in Uganda, the nature of the vacuum created and why that makes the media in Uganda vulnerable to UCC’s voracious appetite for regulatory over-reach.

The media cannot and does not operate in a vacuum. It is a constituent component of the wider eco-system of society and the country’s socio-political and economic life. To that end, it affects and is affected by several dynamics that call for some form of regulation of its own space and the usage of that space. Even the freest societies in the world have a regulatory framework in place. As English author William Golding ably captures in his ‘Lord of the flies’, human beings, left to their own devices, can be a problem when their inherent evil nature comes into play. Everything must be done to save them from themselves. So, institutions such as the church, mosque, family, school, office, and society generally, come into play to regulate human conduct. That is one way to look at it; the philosophical basis for regulation of human conduct is backed by evidence from African Traditional Society to pre-colonial Africa, Asia, the Americas, and feudal Europe. Even among the decentralized communities like the Karamojong, Masai, there existed some form of hierarchy and ordered conduct of affairs in the community. Even animals, as biology teaches us, have some type or form of regulation.

For the media particularly, I find wisdom in English philosopher and political economist John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) who in his celebrated work, ‘On Liberty’ argued that, “The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.” Earlier on in France’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789, the French observed that, “Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights. These limits can only be determined by law.” It is against this background that countries have laws regulating media and limiting freedom of speech and expression on grounds such as hate speech (actively litigated on in South Africa), denial of genocide (in Rwanda), promotion of sectarianism (in Uganda), denial of the Holocaust (in Europe) and a host of other morality and public policy (such as national security) considerations as defined by different societies. You can disagree with these limitations (especially if you deconstruct power through a Marxist lens) but that is just about what there is to ensure that the world is cohesive, its constituent parts do not collapse and there is a balancing of interests, rights and freedoms in the community. This may and usually extends to such civil actions as defamation, privacy breach suits and intellectual property law violations.

We cannot therefore, run away from the aspect of some form of accountability. UCC’s challenge is to persuade the public that it means well and is not using its regulatory prowess to suppress critical media and give the state a free ride by hushing the media in its watch-dog role. Unfortunately for them, even when they sound convincing, they have too much baggage to deal with (including a rather ill-advised decision in 2019 to suspend journalists and editors of radio and television stations over stories the commission felt went below minimum broadcasting standards). In a way, the commission needs repentance and atonement for its past (and continuing sins) in the eyes of the media. The public feels more sinned against by UCC. Before its proposals, directives and actions can be debated on their merit or lack thereof, and not be dismissed as another act of political abuse of the law and institutions of the state by the ruling party and government, UCC should clean its hands and come to the debate cleaner. They can resort to the force of law and state instruments of coercion but to what end? There is more it can achieve by building consensus instead of faking and forcing it.

To achieve that, in my view, and this brings me to the last limb of this argument, UCC must, as of necessity, pull back a little and expend the energy it is currently expending on defending itself into robust industry wide engagements, public consultations and do everything it can to secure buy-in from the critical mass of the media industry. I do not think that UCC for instance, even when it regulates the internet space, has business regulating a newspaper (even if it is an online publication but that is debatable).

Uganda’s media and self-regulation: Where did the rain start beating us?

On its part, the media must debate the question of that desired animal called self-regulation. What is it? How does it work elsewhere? Why has it not taken root in Uganda? What vulnerabilities does its inadequacies here bring and how do we fix it?

Writing on self-regulation, UNESCO notes, “Self-regulation is combination of standards setting out the appropriate codes of behaviour for the media that are necessary to support freedom of expression, and process how those behaviours will be monitored or held to account.”

The benefits of self-regulation are well rehearsed. Self-regulation, UNESCO argues, “preserves independence of the media and protects it from partisan government interference. It could be more efficient as a system of regulation as the media understand their own environment better than government (though they may use that knowledge to further their own commercial interests rather than the public interest).”

Uganda’s media self-regulation is weak and recent efforts such as the Uganda Editors’ Guild (a replica of the Kenya Editor’s Guild?) are yet to bear fruit. Professional associations like the Uganda Journalists Association (UJA) have been hijacked by fortune seekers looking for bread and butter with no convictions let alone across-the-board respectability within the media industry. The senior journalists and editors whose voice and institutional memory matters, have either taken the back seat or left the association to sharks and hyenas, many of them semi-illiterate and career stranded characters whose only claim to the profession is an identity card issued by a radio or TV station owned by a politician or religious group with no interest in journalism and barely pays them a living wage. I say this with the greatest respect to some fine souls in there like the distinguished photojournalist Abu Lubowa who means well but can only achieve so much in a sea of intellectually undernourished charlatans purporting to lead a professional body.

The National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) appears more interested in safe guarding the business interests and survival of the members and least bothered about building capacity for self-regulation. The online publishers have an association that is divided to the bone marrow whose disjointed leaderships do not enjoy legitimacy in this mushrooming segment of new media. Accordingly, standards have sunk to their lowest. The profession is in tatters and gutters. Each media house has been left to its in-house rules and editorial policies. The Uganda Media Council which is, by strict interpretation of the law, not properly constituted, is bleeding to worthlessness as its funding from the state remains a pipe dream. The National Institute of Journalists of Uganda as envisaged in the Press and Journalists Act, 1996 remains a tiger roaring on paper. In short, except in-house editorial leadership which is still strong at NMG (Uganda) especially at the Daily Monitor, NTV and New Vision, Ugandan journalists are operating in a jungle with no standards and rules. Lawyers in the media law practice like myself are sometimes left with no option but advising our clients to count their losses (in terms of reputational damage) and move on because a legal pursuit of the defamatory publisher would surely end in a wild goose chase. I dread oppression and resist tyranny, but I am more frightened by a society where there are no rules and jungle law obtains.

Self-regulation of the media, therefore, is in shambles in this beautiful republic of sweet bananas. There exists a vacuum. Nature though abhors vacuums. Until and unless that vacuum is filled, it becomes an exercise in futility to crucify UCC. Regulation overreach will always be there, and state-media confrontations and contradictions are a permanent feature of most countries. Countries in Africa such as South Africa where the Press Ombudsman is a functional and busy office and where self-regulation is not a slogan but a prominent aspect of journalism, and Sweden where the media’s self-regulation regime and practice makes UCC’s directives look like a slap on the wrist, offer good points of reflection. As Anton Harber, the University of the Witwatersrand Journalism Professor recently said in an interview, “Good journalism nourishes and feeds citizenship and democracy,” but it is also, “an imperfect profession working in imperfect structures in an imperfect society and we need to face up to the reality of what this means.”

Unfortunately, however, and I agree with Prof. Harber when he notes that, “We cannot deal with the issues of professionalism and accountability without solving the problems of the fundamental economic structure of the industry. To be a quality industry, we need to be a strong one, and to do this, we need to find a new way to restore its financial foundation.”

Dear reader, unless and until we have a 360-degree outlook to these issues, we shall continue chasing wind and fearing shadows. The recent crucifixion of UCC, though justified, speaks volumes about the narrow outlook of the problem as only external and not (also) internal (to the industry). There are structural questions that must be answered within and by the industry. There is need to organize before agonizing over UCC’s edicts. Get the house in order first then lay your spears and arrows in defence against the aggressor.

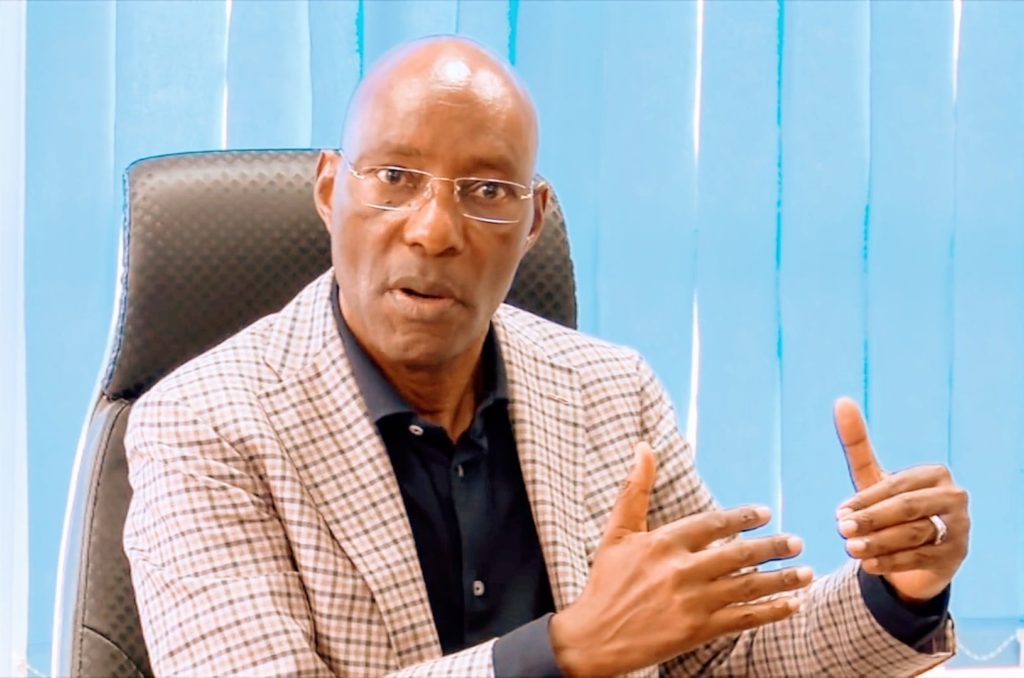

Ivan Okuda is a lawyer with interest in media law and the Managing Editor of Vox Populi (www.voxpopuli.ug), a publication of the East African Center for Investigative Reporting.

Great Narrative..Well dissected